Can You Forgive Me?

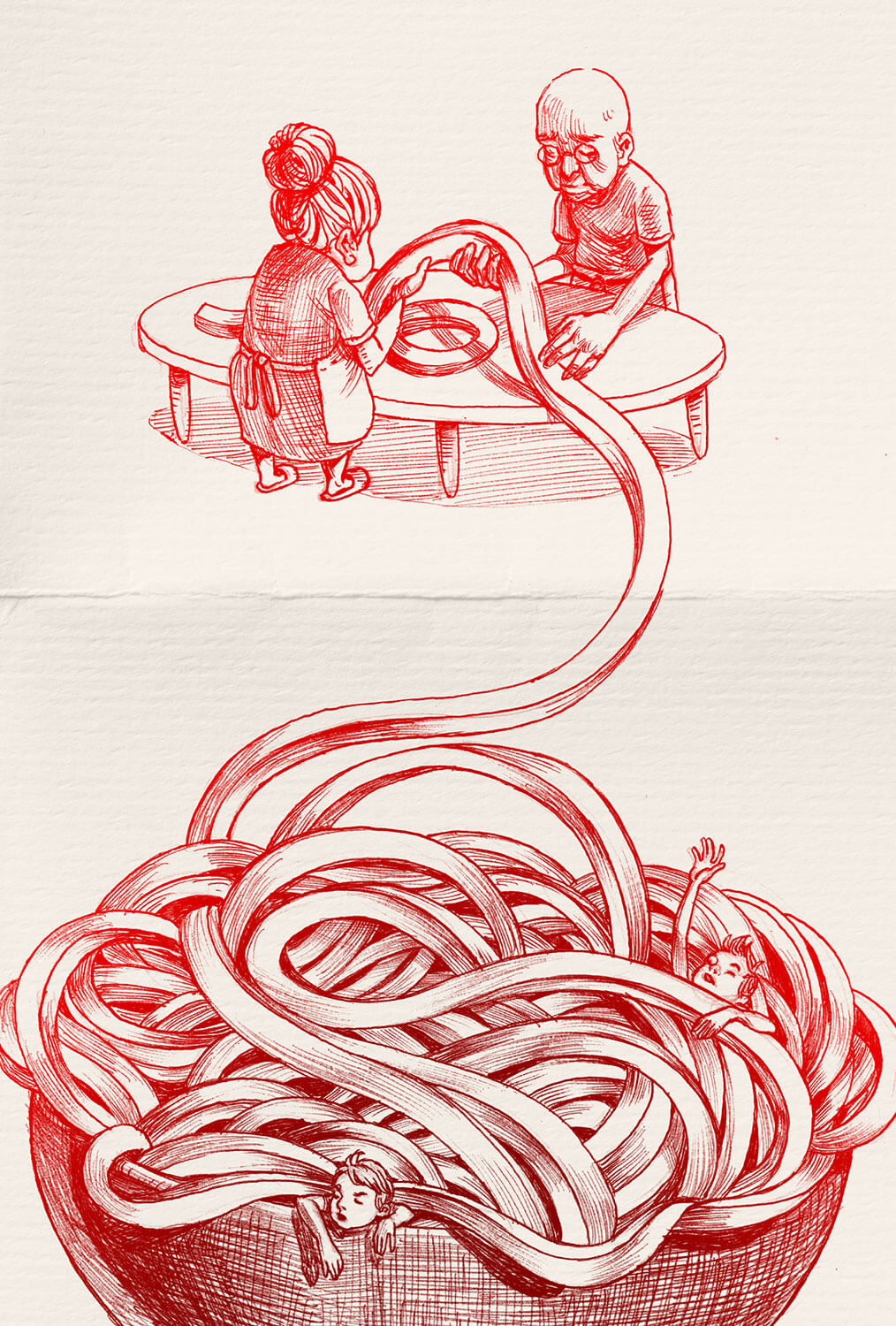

Instead of smoothing over rough edges, forgiveness may be more like origami, with layers of folds and creases that are both delicate and sharp.

I grew up learning that forgiveness was what you should offer someone when they said they were sorry. That it was how Jesus would respond and taught his followers to respond.

There was no question that forgiveness was the right thing to do. It was a given. Expected. But truthfully, I never really understood what forgiveness entailed aside from accepting an apology, let alone the concept of reconciliation.

And so, years ago, when our then editor-in-chief shared with me an ultimatum that he had recently heard, we struggled with what it meant:

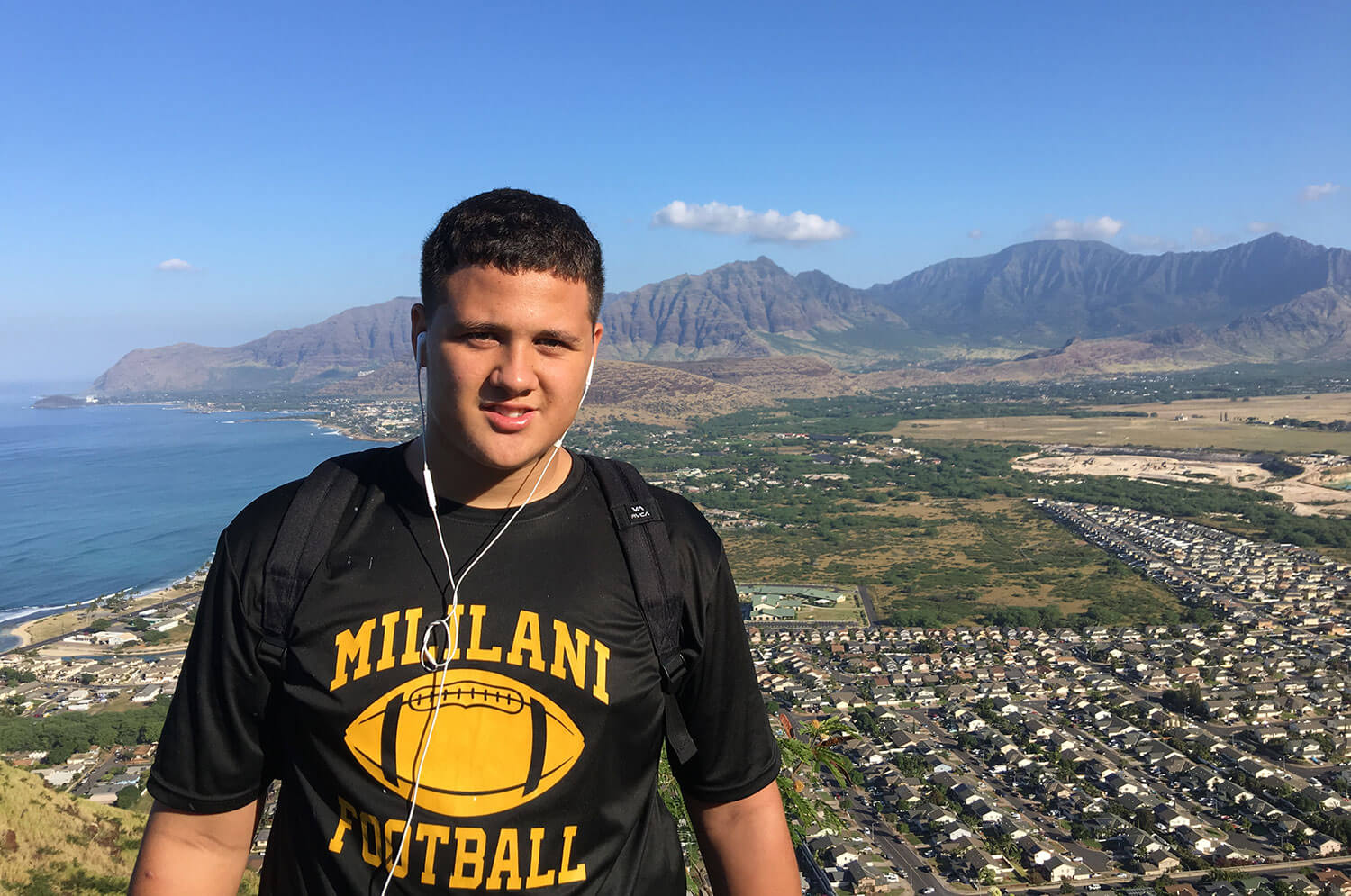

“I can forgive everyone except child molesters, rapists, and murderers.”

On one hand, it was honest and resonant — certain actions are so egregiously harmful, they can never be undone or forgotten.

On the other hand, are there limits to forgiveness? Are people forever defined by their worst actions, or can they be held in their complexities and possibilities? What do we make of Jesus’ saying that we ought to forgive someone 70 times seven times? Does his rhetoric offer a boundary or an unconditionality?

Through the years, even as I’ve firmly held onto the belief that God reconciles all things to God’s self, I’ve also learned that forgiveness is not so clear cut. In fact, considering or even choosing forgiveness often means even more difficult questions and ramifications.

When differences among groups lead to some sort of split, is it possible for people across both parties to continue in relationship amidst fracture and unresolved differences?

Is the end goal of reconciliation for things to go back to the way they were? Or does reconciliation mean coming to terms with a new reality, one in which both parties have made peace with their differences?

To add to its complexities, forgiveness is often invoked as a personal response, without acknowledgment of structural and historical conditions that are not easily reducible to individual action.

When governments or companies fail the people, who asks for forgiveness and whose is it to give? How often are the dispossessed or the oppressed asked to forgive and forget, while hearing that reparations are not politically feasible?

In this issue, we consider the various facets of reconciliation and forgiveness — how we need these relational commitments for our survival, and also how they may fail to address major shortcomings or restoration.

Like a piece of paper that has been folded and unfolded, the creases of harm remain in relationships and communities. Instead of smoothing over rough edges, forgiveness may be more like origami, with layers of folds and creases that are both delicate and sharp.