Six Feet Apart

The fallout of COVID-19 has landed everywhere.

Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.(1)

These days, I say The Lord’s Prayer with more urgency and more confusion than before. “On earth as it is in heaven” feels unimaginable, a single-minded plea in a maelstrom of distress.

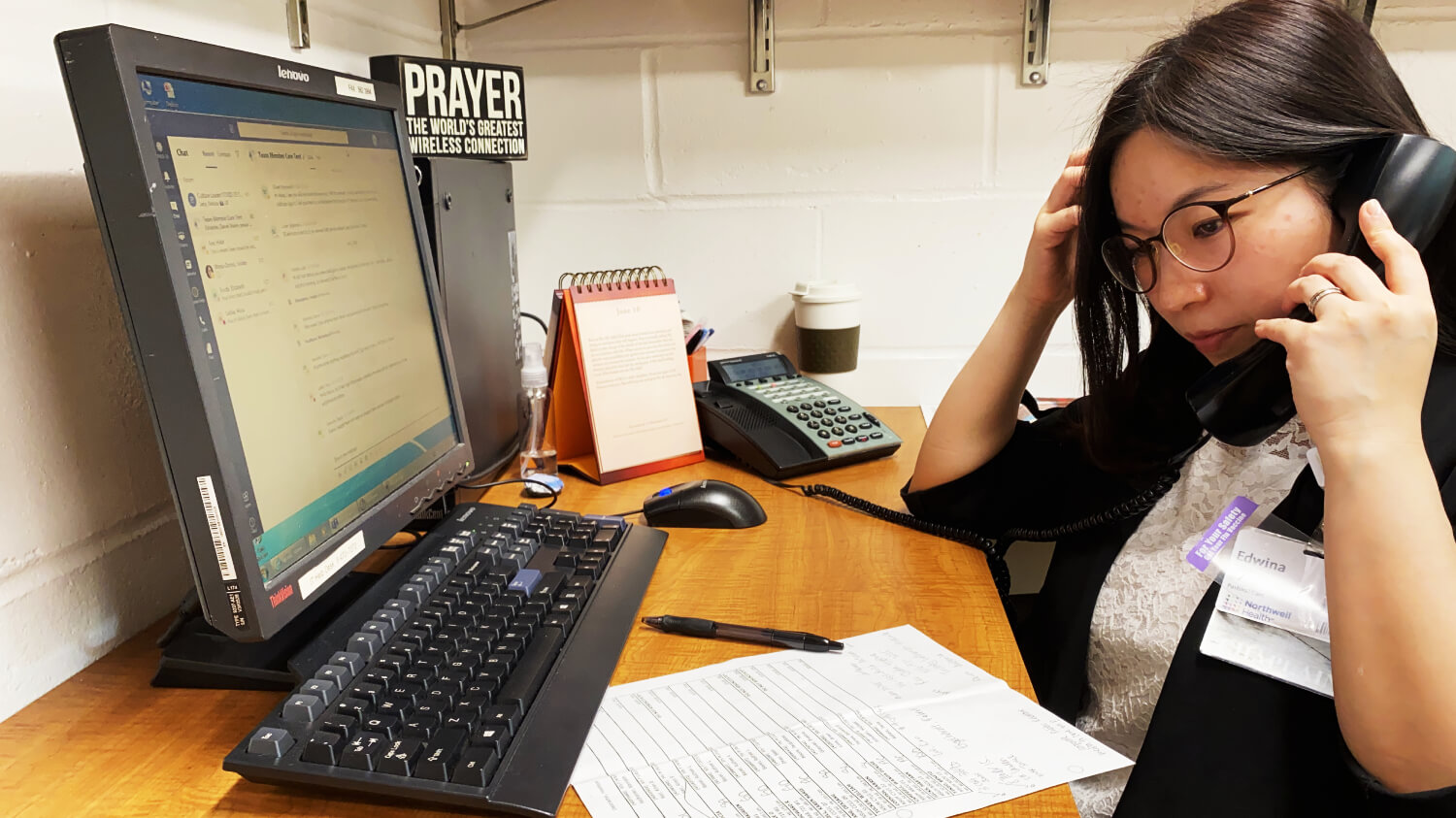

The fallout of COVID-19 has landed everywhere: mental health, mourning, policing, productivity, borders, birth, music, markets, all through which different communities are affected in unequal ways. It’s a common aphorism to say that illness doesn’t discriminate, but discrimination is evident in the impact of COVID-19 on particular communities. Consider the disproportionate number of coronavirus-related deaths faced by Black communities, or the tidal wave of anti-Asian American hate crimes, revealing what was latent beneath the surface.

The stories in this series cover a wide range of topics, reminding us that there is no aspect of life untouched by COVID-19. From the mundane to the monumental, COVID-19’s impacts cannot be pinpointed with one focal length. While that totality is first a cause for grief, it may also be an opportunity for deeper healing and fuller transformation in the months and years to come.

When Jesus healed, he restored the afflicted to their communities. Today, we are all necessarily involved in our collective healing and restoration to community — in care for the elderly, in compliance with social distancing guidelines for those who are able, in solidarity with people whose lives have been thrown into financial freefall. Our interdependence is necessary for our survival.

But hasn’t this always been true? God’s saving work in the world has always been enacted in partnership with humanity and collective human action. We can choose to be part of the process of healing. We can also choose to be part of the process of creation, the act of communal creativity that this era invites with a singular urgency.

For those of us sheltering-in-place, we may feel caught between repose and action. It’s a moment of seeming contradiction — stay home, save lives. In isolation, enact community care. But there’s hope in the contradictions, too. In the midst of physical retreat, perhaps we can renew our commitment to collective transformation, doubling down on a vision of earth “as it is in heaven.” From health care disparities to climate change, there’s more reason than ever to commit to that vision. So we come together in community through stories — to lament, to tell truth, to imagine the world to come.