I write this letter to you with the intention of becoming a good ancestor — to practice e malama pono i na mo’olelo ohana or “taking care of your family stories” by virtue of sharing my own. This is a letter but it is also a kaʻao, a story intended to pass on history and culture.

Long before mo`oku`auhau (genealogy) became a billion dollar industry, the line of descent traced from one of our ancestors to the next was considered spiritual. It was a gift, a responsibility, and an integral part of Hawaiian identity. Our genealogy wasn’t about DNA so much as it was a way of connecting with one another, and to the land, or ‘o ka pae ‘aina Hawai‘i, as our true homeland. Historically, Native Hawaiians were taught our genealogy through family exchange. The hiapo (first child) was given to the grandparents and charged with learning the oli (chant) of their family’s ‘aumākua (family god or deified ancestor). This practice was a part of other lifelong rituals that ensured the family’s history would be preserved as the generations grew. Rather than this practice serving as individualistic knowledge and pride, a family’s history was a means of communal flourishing. To know your ohana was to know where you come from, and to know where you come from was central to the enfleshing the spirit of aloha (love) in the world.

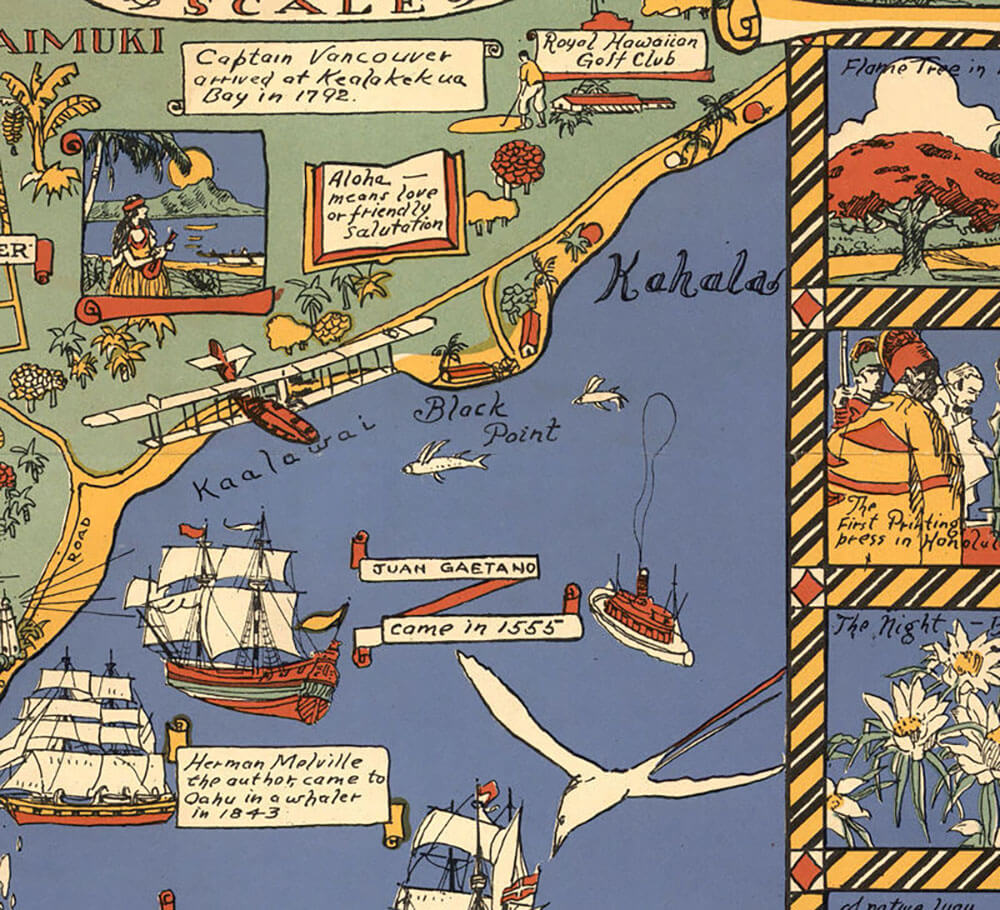

Aloha, far more than a greeting or farewell directly translates to “the presence of breath” or “the breath of life”. It comes from “Alo”, meaning presence or front facing, and “ha”, meaning breath. Aloha is mutual regard, affection, and the extension of care without obligation. Aloha is the essence of relationships wherein each person is important to every other person for collective existence.

Admittedly, I write you this letter as an ancestor who has, to date, only ever lived in diaspora. Imperialism and colonialism brought complete disorder to our peoples generations ago, disconnecting us from our histories, the ʻāina (land), our ('Ōlelo) language, our social relations and our ways of thinking, feeling, and offering hospitality. My own parents raised our family thousands of miles away from Hawai’i, gave us English names, socialized us in predominantly white neighborhoods and churches, and tried to sell us on the American Dream.

In the words of spoken word artists, William Nu’utupu Giles and Travis T. in “Oral Traditions”, “I was born with the pride of my history but no knowledge of my language. Speaking of the pride of a skin I lived with but not in.”

Consequently, my life has revolved around misidentification; my heritages, my gender, my sexuality, and various other axes of being were all wrongly ascribed to me and I assimilated accordingly. I commemorated only the cultures of Western peoples and consequently accepted the myriad of negative health outcomes associated with generational and religious traumas as simply “my lot” in this life. I was living with severe depression, anxiety, grief, and anger. Even though I had left the evangelical ministries perpetuating exclusion, I couldn’t shake years of being conditioned to valorize suffering. I continued to hate myself, to feel isolated, and to struggle with other symptoms of PTSD like night terrors, flashbacks, dissociation, and extreme daytime fatigue. I didn’t know life could be different and I nearly gave up believing that I would ever be able to heal or be well.

But in 2014, my story turned a corner because of someone else’s story. I was 24, living in Topeka, Kansas, and working for a secular nonprofit. I slipped into the back row of a small theater during the Kansas City LGBT Film Festival and saw the life and work of Hinaleimoana Kwai Kong Wong-Kalu, Native Hawaiian kumu (teacher) and activist, projected onto the big screen. By this point, I had read critical race and gender theory, I was immersed in mainstream queer culture, I had even begun to unlearn the cultural myths I had inherited through U.S. public education regarding the history of Hawai’i — but something shifted for me through the medium of audio-visual narrative. I watched Kumu Hina describe her past, present, the communities she belonged to, the multiple cultures she held, and various languages she knows and teaches not as merely places of marginalization, but as sources of resistance and hope. And from within, I felt the tectonic plate slide over a plume of magma, puncturing the crust and forming a volcanic-like eruption in me.

Sitting in that movie theater, Hina’s story challenged me to seek out more stories that do not get airtime, to put my body in new places and new communities where personal experiences are treated as an authoritative source of knowing, and in so doing, generational power is invoked. I began to re-member our ohana — that is, to try and put back together our peoples and stories that have been scattered across space, time, and geopolitical boundaries. While my path has been fraught with frustration, insecurity, and feelings of not being “enough”, I’ve benefited from the words of other diasporic indigenous peoples who remind all of us that just because our practices of re-indigenization aren’t linear or perfect, doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t pursue them at all.

Who I am and where we come from didn’t click for me until I heard it narratively, and I would later learn this was not by accident. As it turns out, many indigenous genealogies are only transmitted in stories. Our genealogies write themselves in traditions and often don’t “write” themselves at all. They are told, they are shared, they are lived. You and I come from peoples who pass and share wisdom, lessons, and riddles as a way to survive, heal, and thrive. You come from ways of life that recognize the balance, respect, and mutuality found in all of creation, and this is completely independent of blood percentages or what “parts” you are of this lineage or that lineage. You are whole. Unified. Integrated. Identifying in parts is the language of white supremacy, the One Drop Rule of anti-Blackness, and broken land treaties based on a “certifiable” degree of Indian blood. May you take no part in this.(1)

Whether you ever look for these stories or not, passing our genealogy on to you has given me hope and direction. It has created the conceptual space to work on my trauma, to develop practices that recognize the wisdom and aliveness of all the created world, and to look for solutions to the problems of living in a post-industrial globalized world in my body, and not just in books.

There may be times when this feels like an impossible puzzle you did not ask for, but if in your searching, this letter is all you find, please know this:

There is a place where you are fully known, where you are seen, and where you are loved. There is a place where you belong. Whether you or I ever learn her language, return to her ocean, or participate in her rituals, that place is in your iwi (bones) and nothing will ever change that.

I am confident in this because when I began to affirm the goodness of my body — of my indigeneity, my gender identity, my sexuality, the sound of my voice, my mannerisms, and everything in between, that is when I began to believe that feeling home could be possible. I am confident in this because I feel it against my own skin every time I dive under crashing waves. I feel it in my lungs every time I breathe in plumeria flowers and maile leaves. I feel it rush through my veins every time our music helps me to manage my anxiety disorder, and I taste it on my tongue every time I say my own middle name. I pray that if ever you should feel lost, it will be because of your body and not in spite of it that you begin to find your way again.

With Aloha,

Myles Kaleikini Markham

Myles Markham (he/him or they/them) is a graduate of Columbia Theological Seminary, the Impact Producer at Multitude Films, an LGBTQ women-led independent documentary company and the Screening Manager for Story Productions, a non-fiction film ministry of Presbyterian Disaster Assistance. Previous to their work in film, Myles served as a faith organizer and consultant on LGBTQ inclusion and racial justice in evangelical and conservative communities for five years.