Arirang is traditional Korean folk music that has been passed down by memory for over 600 years. It wasn't until 1869 that Christian missionary Homer B. Holbert went to South Korea and scored it black and immutable onto paper for the first time.

Arirang, Arirang, Arariyo

Crossing over Arirang Pass.

Dear who abandoned me

Shall not walk even ten before their feet hurt.

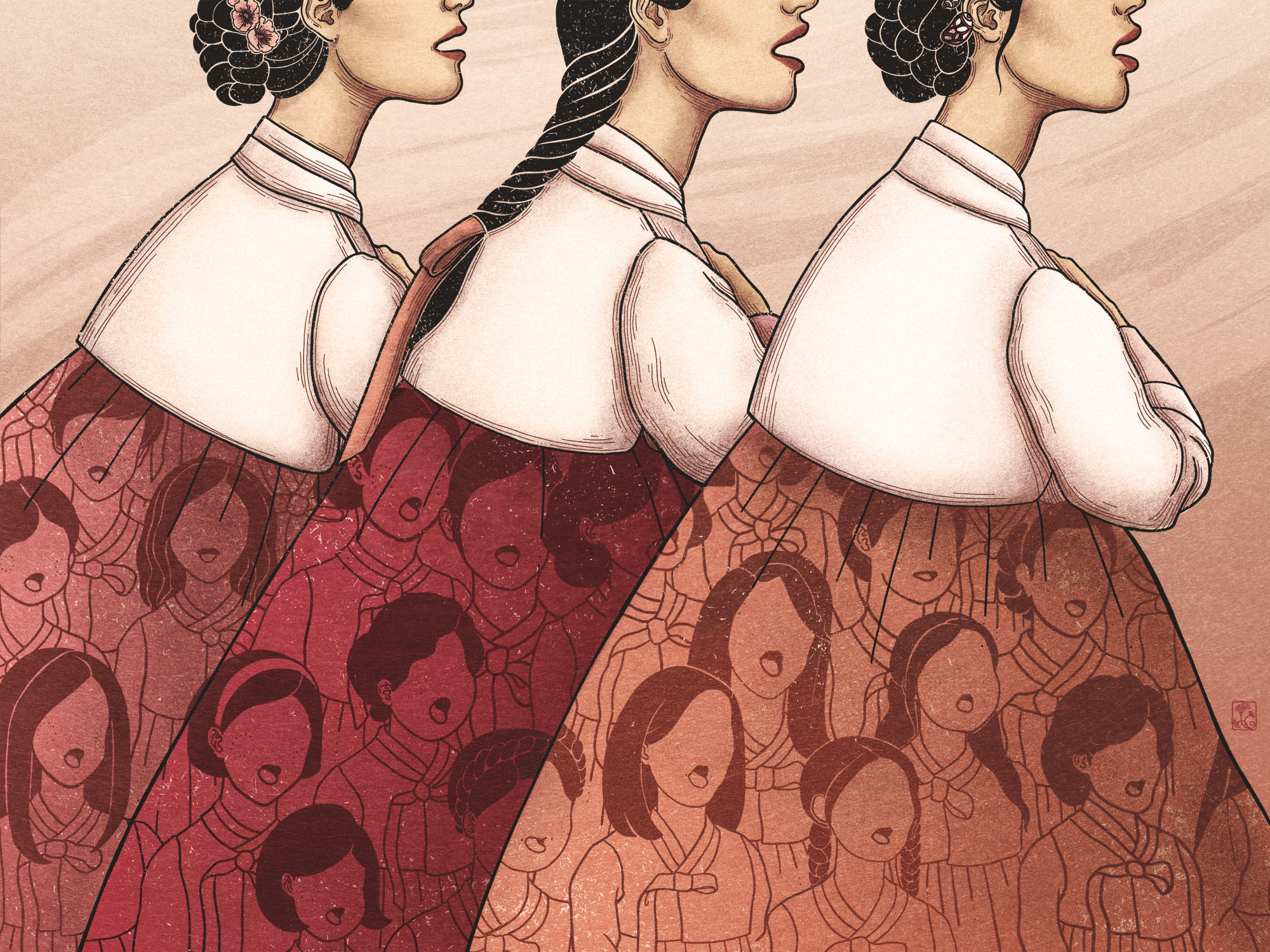

The music translates yearning — one that can hold pain and joy at a deep simmer. Hulbert allegedly observed that arirang is like rice to the Koreans: Just as people eat every day, people sing arirang every day. They carry it beside them at all times: an inherited legacy of a history of division and subjugation.

What was once like rice to Koreans is now forgotten at best by the younger Korean generations living in South Korea. On the U.S. end of the diaspora, most Korean Americans cannot claim ever hearing arirang in their lifetime. Younghae Kim’s life is a yearning for this music, which has taken her on a journey from South Korea to the United States and back to South Korea again.

The irony is that she had to go to America to find a value for Korean music. As a mother, a musician, a Korean, and an American, Younghae is trying to remind her people of a sound that is uniquely their own, saying, “Arirang means having a collective identity. It’s not something personal, but something for all of us to feel.”

• • •

Younghae first recognized the value of arirang when she had to suspend her pursuit of a doctorate in music. She and her husband moved to Missouri in 1997 because her husband was transferred to the geophysics doctorate program at the University of Missouri in Rolla. But there was no music department for Younghae to continue her studies.

A year after they moved, their first son, Daniel, was born, followed by Calvin 2 1/2 years later. Through it all, Younghae says, “I didn’t give it up. I thought I’d always continue, I just kept keeping up with it, little by little.” She participated in choir. When the children were sleeping, she composed music. She taught music lessons in her spare time.

Arirang found a champion in Younghae as she spread it to all her communities: her family, her church, and the two countries that she calls home. “I’m Korean and I wanted to show other people, ‘This is what a Korean sound is. The music had a quiet trumpet, and when it sounded, people cried. It moved people together.’”

Younghae went on to organize joint music performances in the university and in her church. She brought youth on instruments and parents with their voices together in harmony, a physically and musically united body in the face of the miscommunication and misunderstanding that so often characterizes the relationship between generations.

Younghae eventually moved back to South Korea because she wanted to teach and work at her alma mater and country — a move that’s typically made in the reverse for her generation — but she noticed that both in the U.S. and in South Korea, there was a yearning for something truly Korean.

During Japanese colonization, Korean music was prohibited, degraded, and despised as low-class music. The rapid Westernization of South Korea that followed developed a music education predominantly focused on Western music and history. Younghae recalls having to learn Johannes Brahms and other deceased, Western composers, with no mention of Korean musicians. In Younghae’s eyes, South Koreans are now more comfortable acting American than being Korean, forgetting even their own music. “We’re not singing our own songs! Let’s try singing our songs well, for once. Western music doesn’t quite fit us,” she says.

“Arirang is a music of yearning, and we are a people of yearning; we’ve lost our country, we got it back, but today, it still looks lost. We’re in wartime — people have forgotten that, too — and we are not complete,” says Younghae.

She recognizes this yearning for wholeness in her faith as well, as her words resound with language used to describe how Christians long for a day when the redemptive work of Jesus is completed.

She asks: “Why did God make us Korean? That is a worthwhile question. Then we can develop our ethnic tradition alongside our faith. It may look separate, but we all come from somewhere. We’re to reach the world, through anything in addition to words, so we must develop both our tradition and our faith simultaneously.” In a similar fashion, she cites how she believes that Paul was born Jewish in order to reach the Jewish people — his own people — who denied Jesus.

Now, Younghae is working to build up a system to help South Koreans and Korean Americans value their identity through Korean-spirited music apart from Western influence. Her children are ever at the forefront of her mind, hoping that those of her sons’ generation might forge a connection between their ethnic identity and their parents and grandparents through music — be it through shared singing sessions over Skype or public performances.

She reached out to Calvin’s high school Korean language teacher in the U.S. for help in educating youth about Korean culture and history through music. That Korean language department went on to watch Younghae’s music performances on Youtube, and has started to translate them into English to re-upload the videos with subtitles so that the world might know their meaning. Other community entities that range from government bodies to senior choirs have also expressed interest in partnering with her vision.

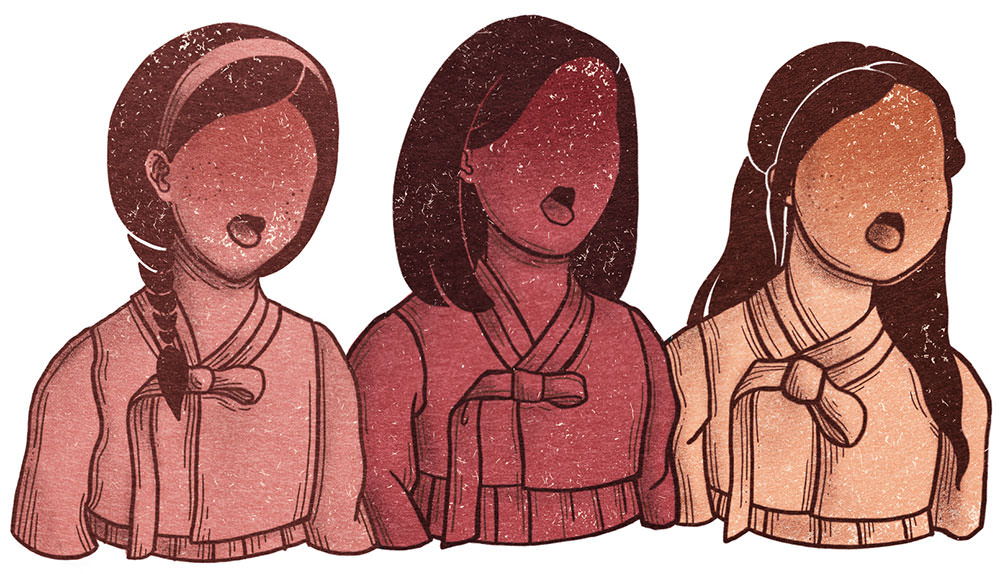

Another of her many endeavors includes supporting Arirang Chorus Seoul, which in its repertoire includes a cantata titled “My Country”. In five movements, it conveys the history of Japanese colonization, the injustice of comfort women, the independence movement, and how arirang is sung today.

With her eyes on Arirang Chorus spreading to other cities, she is planning a 2018 concert that will involve both Koreans and Korean Americans. Younghae says: “I’m doing the work of telling my sons the good things they have inherited. Let’s reflect about what we’ve done for the next generation. For goodness sakes, what did we do? Eating and surviving got too busy. We didn’t convey who we are to them.”

• • •

What Younghae has given her life to is a question that faces all Asian Americans: How much of your culture do you have and how much of it do you want to pass down? Younghae strives to be a role model first so that her sons might see and love who she is, that they might want the music for themselves.

“Parents want to be known, too. It requires personal effort and systemic effort. Hard, but parents have that heart; it doesn’t get expressed well though. But with arirang, whole families can feel a collective feeling, resonate with the feelings and thoughts of the earlier generations, and know what kind of people they are a part of.” Her hope is that South Koreans, Korean Americans, and people at large might know that Korean music is an option at all, that it is there to tap into as a means to express an incompleteness that cannot be put into words.

It is witnessing the fruit of people accessing arirang that keeps Younghae moving forward: “With LA Remnant Chamber Orchestra, my youth sang songs that their grandmothers enjoyed. One was called ‘Gah Go Pah’ or ‘I want to go to my hometown’. And the kids resonated with it. They were crying, even though half of them couldn’t understand the words. They felt it — a collective feeling. You can’t teach that, and they won’t ever forget it — this tool or memory that they can keep.”

Arirang inevitably takes on the nuances of where it is sung as it is passed down, and many versions of arirang have emerged from the diverse regions of South Korea and the different times it has survived. Arirang reflects the pulse of the generation that sings it, while the consistent melody maintains a familiar thread through the generations. As American as her sons are growing up to be, Younghae hopes to see that they feel pride in being Korean, too. She invites them and their peers spread across the world to uniquely express their arirang with the dreams and wholeness for which they yearn.

Sarah D. Park (she/her) is a second generation Korean American born in Los Angeles, CA. Her work reflects her value for finding abundance in community and the power of telling our own stories. She’s currently based in NYC and spends her time eating cheeseburgers, creating community spaces, and enjoying her son.

Carlene Younghae Kim is a conductor born in Seoul, South Korea. She received her bachelor’s degree in music at Ewha Womans University in Seoul and a master’s in music at the New England Conservatory in Boston, Massachusetts. She earned her doctorate of musical art in choral conducting at University of California, Los Angeles. Currently, Younghae is teaching conducting at Ewha.