“You guys are all so rich, Dad says, pointing the remainder of his sandwich at us accusingly. You’re barely Cambodian. You’re barely Cambodian-American! Just remember, he adds, remember where you came from.” — Anthony Veasna So

In the 1910s, in his early 20s, before 泽东 became 主席, Mao Zedong spent six months at the library, arriving the minute the doors opened and leaving the minute they closed, reading with the voraciousness of a peasant’s son who understood the preciousness of time and space to sit and think. His father, Mao Yichang, wasn’t just any peasant, but a rich landowning peasant, which meant he was a tyrant; his mother, Wen Qimei, was a gentle Buddhist who tried to temper her husband’s wrath. When Yichang found out about Zedong’s studies at the library, he cut off his son’s allowance and told him to get a real job, which he eventually did: Chairman of the People’s Republic of China.

In the late 1950s, Zedong confessed to a close friend and advisor, “I have no idea how to build a communist state.” It’s comparatively easy to start and even complete a communist revolution — that’s just destruction. A communist state, however, requires creating not just a new political order, but a new reality. To quote the Chairman, “If you want knowledge, you must take part in the practice of changing reality. If you want to know the taste of a pear, you must change the pear by eating it yourself.”

So Zedong wracked his brains and thought of England. How did the Brits take Hong Kong from China in 1842? How did this tiny island of pasty-skinned people steal the “Pearl of the Orient”? After a bit of thinking, Zedong came up with a simple equation:

Population x Technology = Output

England’s population was tiny, but its technology was extremely advanced, which resulted in massive output. Zedong understood that China’s strength lay in its population; at an international meeting of communist parties, he offhandedly remarked that since China had 700 million people at the time, if nukes wiped out half the population, there’d still be 350 million people left, and that from a purely economic standpoint China would actually benefit from nuclear war.

Stunned silence followed.

A representative from the Italian communist party asked Zedong what would happen to Italy in the case of nuclear war. He replied, “Italy doesn’t matter.”

Once he figured out the equation, Zedong realized China was golden. Its rapidly developing technology would combine with its still-growing population to result in near-limitless output. But Zedong didn’t want to wait — he didn’t want anyone else to experience the deprivations of growing up as a peasant’s son. So he thought about what China’s output should be, and he chose 铁, and obviously iron = strength, but maybe he also thought of his mother cooking him red-braised pork with the cast iron pots and pans that can be found in every Chinese kitchen in the world.

In any case, Zedong told the people, the Chinese people, his fathers and mothers and brothers and sisters and sons and daughters: “Listen. My people, my family, my flesh, my blood: I have an idea that will change reality. It’s simple, really, there are only two steps:

- Stop farming.

- Melt all your iron pots and pans into raw metal.”

From 1958 to 1962, 45 million Chinese people starved to death.

• • •

You haven’t heard of Henan, Xinyang. People in China haven’t heard of it. Xinyang was the epicenter of the famine — something like 12% of the population died. It’s also my dad’s hometown.

There are personal testimonies of parents killing and eating their children. My grandmother was young at the time, which in a society that valued sons, meant she was less than worthless. Her mother — my great-grandmother — had died before the famine from natural causes. Her father, however, was still alive, and at some point, as the city ran out of rice, and dogs, and grass, and leaves, and tree bark, and clay, he must have looked into his daughter’s eyes and made a choice.

My grandmother watched her father starve to death.

• • •

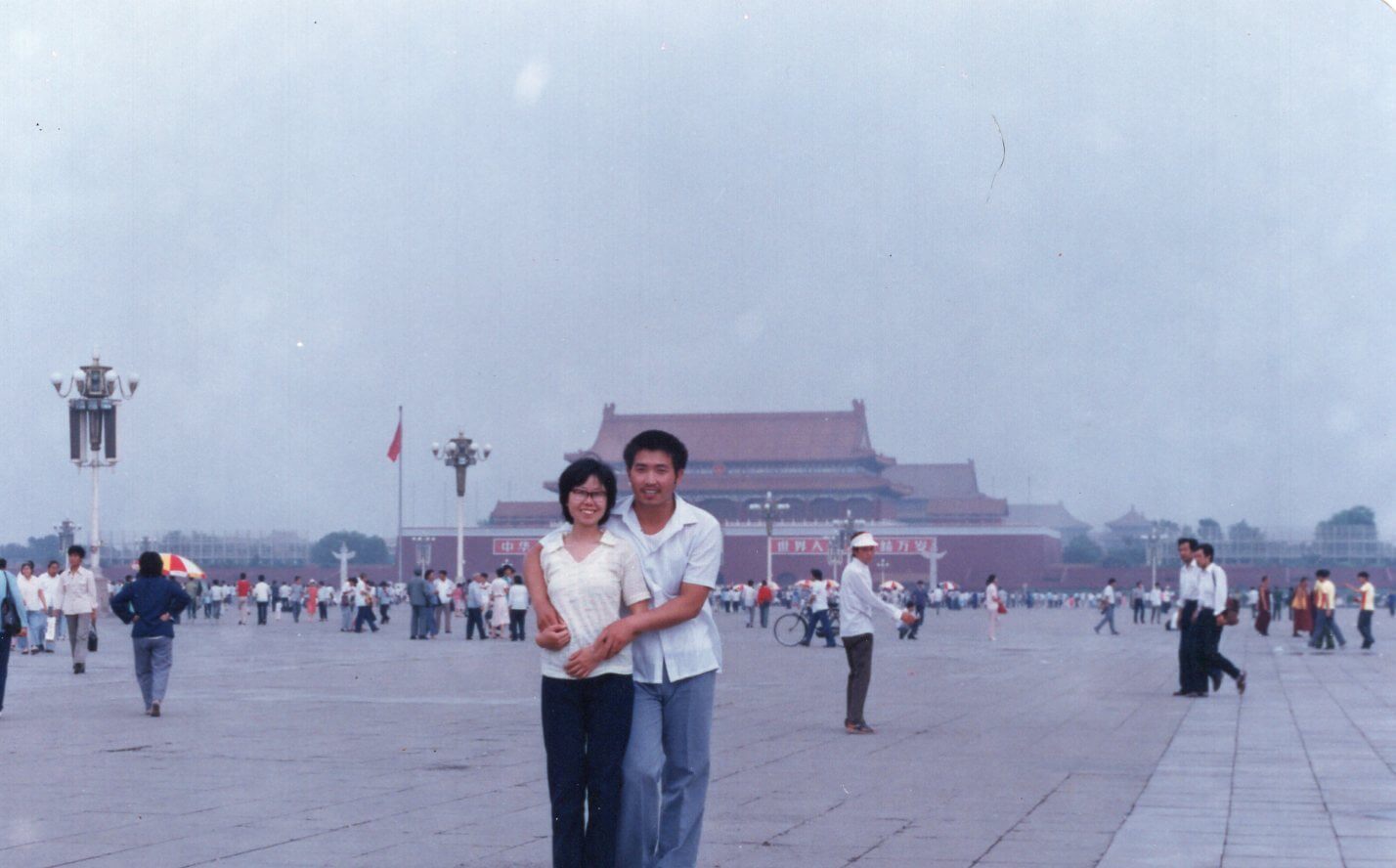

The Chairman died in 1976; the country “reformed and opened up” in 1978; my parents met at Peking University in Beijing in 1985. They were the lucky ones — nothing people from nowhere towns who managed to find jobs in state-owned factories considered 铁饭碗: iron rice bowls that would provide lifelong employment, healthcare, and housing. In other words, they were stuck in what they experienced as meaningless jobs with conditions that seemed to have no chance of ever improving, so they did what all their friends were doing and applied to grad school overseas.

In the spring of 1989, my dad was admitted to the University of Oklahoma’s Ph.D. program in biochemistry. In June, the People’s Liberation Army killed hundreds of people in response to protests at Tiananmen Square. In August, my dad arrived at the Will Rogers World Airport in Oklahoma City.

He didn’t know anyone. He was a stranger in a strange land. He was nobody from a town nobody had ever heard of, a town where one in eight people starved to death because a man loved the idea of people more than people themselves.

A white man approached him and smiled. “Hello”, the man said, “my name is Dave.” (Dave isn't his real name.) Dave said he was from a local church with a Chinese student outreach ministry, and that he could drive my dad to his new apartment. Dave gave my dad a Bible, which he read every day; it was the first book in English that he read cover to cover. My mom arrived four months after him; they attended the same Ph.D. program, ate the same purple cabbage and egg stir fry for dinner each night, spent late nights grading exams (work that the tenured professors they TA’d for were far too busy to do), and went to Bible studies led by Dave 爷爷 — Grandpa Dave, as my parents told me to refer to him.

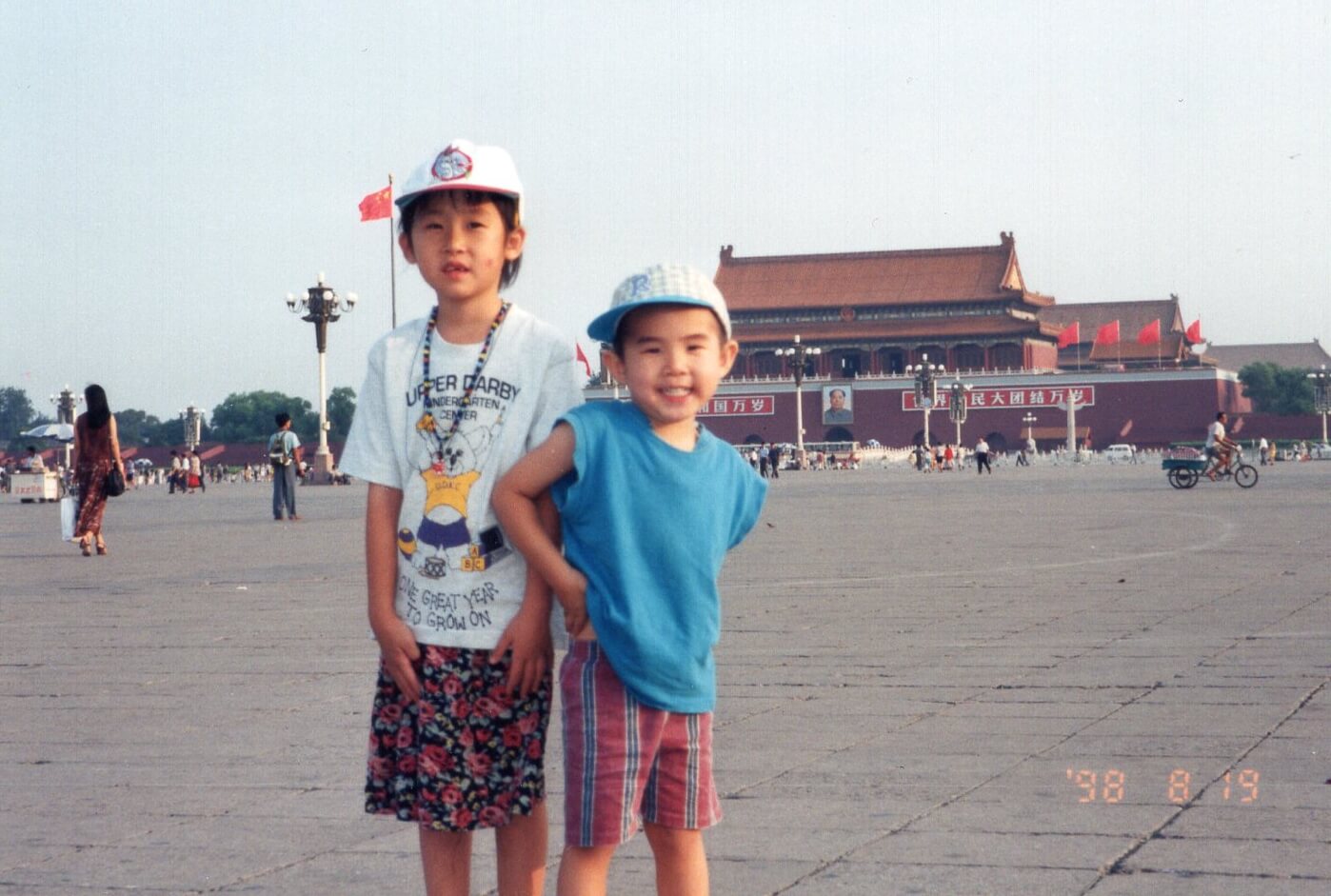

They got baptized together. My sister was born in 1992; I was born in 1995. We were both baptized at birth. My mom chose our names. My sister is 小蒙 (Xiao Meng). 小 as in small, because it’s a common Chinese name, but also because my mom says she’s been blessed by God since she was small. 蒙 as in 蒙古 (Meng Gu), Mongolia, because my mom is from Inner Mongolia.

My name also has two parts. The first is 博 (Bo), which is part of the phrase 博士 (Bo Shi), which means Ph.D., which makes sense, but 博 is also just a nice word: erudite, overflowing, abundant. The second is 恩 (En), which means grace, which to them is a very Christian word, but it’s also part of the phrase 蒙恩 (Meng En, the same Meng as my sister), and that means to show favor upon someone — like if the emperor was about to execute a criminal but decided to spare him, or if a starving father in the midst of one of the worst famines in world history looked at his daughter and decided to starve himself — that would be an example of 蒙恩. My mom thought that collectively, my sister and I are an example of God showing favor upon us poor sinners.

And lastly, if you put it all together, I am Boen, Bo En, 博恩.

I am Bestowed With Abundant Grace.

Boen Wang is a writer, audio producer, and MFA candidate in nonfiction at the University of Pittsburgh. His audio work has won the “Best New Artist” award at the Third Coast International Audio Festival, and his written work has appeared in The Fourth River, PopMatters, and elsewhere. Visit his website at boen.cool.