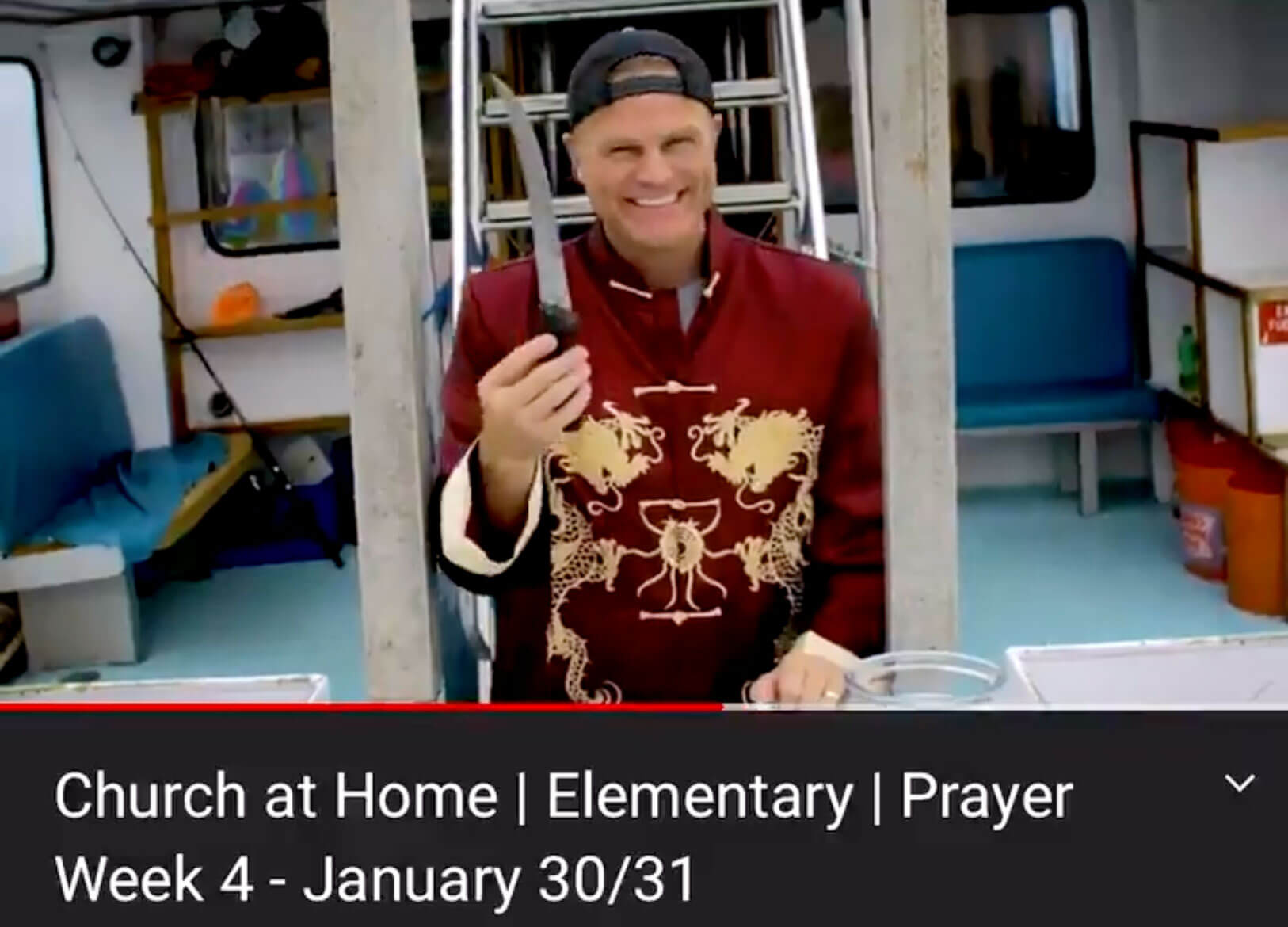

Editor's note: We recognize the violence that this image represents, the ways in which orientalizing racism continues to perpetuate, by a white American evangelical behemoth in this case. We post this image not to reinforce, but to recognize and counter attempts to remove and erase this incident by Saddleback, which is not the first to take place.

Oops, you think I’m in love, that I’m sent from above. I’m not that innocent. - Britney Spears

When I first arrived at university, it felt like every Christian I knew was reading "The Purpose-Driven Life". I remember this clearly because I convinced a girl from church to go to the mall with me by calling the would-be date “purpose-driven shopping”. We had fun, but then she said that we should just be friends. I got into John Piper and became an angsty “man of God” instead. It had, after all, not been my only purpose-driven dating failure. There was another girl I tried to get close to before I went to college. She went to a multicultural megachurch that even had painted on its walls the baseball diamond Warren used to illustrate all the bases one had cover to secure commitment in the process of “disciplemaking”. I got friend-zoned that time too.

What I am getting at is that Warren was literally everywhere, as ubiquitous in the Asian American evangelical world of the early 2000s as Coldplay, Michael Bublé, and Josh Groban. You couldn’t even get baptized in those days without getting a copy of "The Purpose-Driven Life". That’s how much of a "New York Times" bestseller it was in 2004.

College is a long way behind me now, but all these memories of the sins of my youth are flooding back to me because, of course, Rick Warren and Saddleback Church have become all too relevant yet again in the past week. They’ve managed to do once more in 2021 what they did twice in 2013. They have a seeming penchant for publishing orientalizing material that gets Asian American evangelicals riled up.

Last time in 2013, Rick Warren posted a smiling picture on his Facebook of a Red Guard that he thought was funny. The Asian American evangelicals who saw it did not. It took him about two weeks to apologize, and when he did, he said it was “if” we were offended. Three weeks later, a church-planting conference included a "Karate Kid" sequence in a training skit with white people parodying Asians. Asian American evangelicals (including me) authored a series of blogs that culminated in a document signed by over a thousand people, titled “the open letter to the evangelical church”.

This time in 2021, the children’s pastor at Saddleback recorded a video where he was dressed up in what looked like generically East Asian clothes, sliced up a fish while making kung-fu fighting noises, put a raw piece in his mouth, and spit it out in disgust. A series of posts was published on the website of the pandemic-era collective Asian American Christian Collaboration (AACC). Unlike in 2013, the apology this time was swift. Warren clarified that the video had been made four years ago, doubled down on Saddleback’s vision to be an “All Nation Congregation”, and referred to the guy in the video as the “former Kids Pastor”, though when his emeritus status had been earned was unclear from the statement.

Let’s take as given that orientalist imaginaries are racist, that some Asian American evangelicals were offended enough by it to call Saddleback out for it all three times, and that the varying levels of apology from the church after they got caught those three times have enabled three different degrees of reconciliation for the kinds of people interested in that kind of thing. I’m not really interested in litigating any of those items, although there was a fair bit of online controversy back in 2013 among Asian American evangelicals on how we publicly confronted Warren and probably some discontent going around now that, oops, they’ve done it again.

In fact, there is also now a history of over 16 years of Asian American evangelicals writing on the Internet since 2004 about how white evangelicals have orientalized them in Vacation Bible School curriculum, popular books sold at Christian bookstores, social media posts, church-planting training skits, reception to chapel talks, denunciations of “social justice” and “critical race theory”, anti-Asian racism during the pandemic, U.S.-China relations in light of the January 6 Capitol coup, and the current children’s Sunday school material debacle. There’s even academic scholarship on this stuff now, including two book chapters I’ve recently written for some scholarly edited volumes in spiritual geographies and digital religiosity in Global Asia.

None of this, in other words, is new. It’s not like Asian American evangelicals are finally rising up or whatever, because you can only say that so many times about something that keeps repeating itself for over more than 16 years. The same thing goes, by the way, for "Crazy Rich Asians". It’s a fun movie. I happen to truly love it, especially because it completely fails to understand anything about Singapore, where I work across the street from the “church” where the wedding happens (it is actually a convent façade populated by bars, fusion food, and Japanese restaurants). But it’s not like it’s some representational watershed either. Really, it was just a 2018 update of "The Joy Luck Club" and "Flower Drum Song", a bit like how every generation gets their own version of "A Star Is Born". If you want the 16-year details of Asian American evangelicals doing their thing online, you’re welcome to read my scholarly writing, or what my friends like Helen Jin Kim, Jane Hong, and SueJeanne Koh have written. And if you want an Asian American romcom that doesn’t just repeat old tropes, try "Eat a Bowl of Tea". It’s about erectile dysfunction.

To return to Saddleback, I’d like to offer some personal considerations, stuff that doesn’t always make it into my academic writing. In particular, I want to consider why it is that Asian American evangelicals, including me when I was one (I’m Eastern Catholic now; long story), care this much about Rick Warren and Saddleback Church. They’re not the only person and place that Asian American evangelicals have spent over 16 years writing about with regards to orientalism. But they do show up an awful lot in this saga.

This interest, I think, drives us into the realm of what the poet Cathy Park Hong has recently called “minor feelings”. These are the feels, she says, that nobody but me and my minority, non-white communities care about. Take these “minor feelings” out to the world outside of your particular minority community, and the who cares question arises almost immediately. For Hong, that is why she writes with a mix of cringe and nostalgic delight about her childhood church in Los Angeles’s Koreatown. It was full of what she calls “bad English”, she says, weird grammar as a given, but also loaded with appropriations from American popular culture — sitcoms, hip hop, indie rock, stand-up, and so on — mixed with Korean words. Here, the minor feeling I’m talking about is that there are a lot of Asian American evangelicals over the years who have wanted their churches to be Saddleback Church. It was part of the material we cobbled together for our world, which, again, is why even I at the time was using "Purpose-Driven Life" quotes as pickup lines (not that any of them worked).

Maybe that’s hard to understand unless I tell you more about just how ubiquitous Warren was in my Chinese Christian world growing up. I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area in the mid-1990s. There was a Chinese church near where I lived that followed the principles of church growth from "The Purpose-Driven Church". They got themselves so intertwined with the local economy that they were integral to the town’s transformation into an Asian “ethnoburb”, as the urban geographer Wei Li calls them. (If you like “ethnoburbs”, you can also read Wendy Cheng’s and Willow Lung-Amam’s books.)

The same was true of Chinese evangelicals in Vancouver, where I went to college. The pastor at the English-speaking, second-generation congregation I attended tried to do one better than Warren. He preached often that it was not enough just to make disciples, as Warren taught. “Disciplemakers are called to make disciplemakers,” he would say. He eventually planted his own Chinese Canadian church, and when he did, he did what Warren said to do. He identified a target audience — mid-career Chinese Canadian English-speakers with families — did his market research on the kind of family-friendly environment they would like, and framed everything at the congregation to be sensitive to that “seeker” demographic.

Looking back on the blog posts some of us wrote in 2013, I’d say we really were leaning into these minor feelings. Eugene Cho, then the lead pastor of Quest Church in Seattle, said that there were especially three to read about the matter, for starters: Kathy Khang, Sam Tsang, and a mysteriously anonymous blogger called Chinglican at Table (actually me). Cho had had some experience writing about orientalizing racism in the white evangelical world. In 2009, he had spearheaded a campaign to get Zondervan to pull a book titled Deadly Viper Character Assassins", which portrayed sinful temptations as ninjas out to get you. Actually, it was a parody of the "Deadly Viper Assassination Squad in Quentin Tarantino’s "Kill Bill", but that was also the point. What might have been funny in white supremacist American popular culture as a parody of Asians also implied that Asian Americans, who are allegedly part of the same evangelical world that advertises how “Jesus loves the little children / all the children of the world / red and yellow, black and white”, weren’t real people.

That’s exactly the tragedy that Kathy Khang wrote about on her first post on the 2013 Warren saga. Warren, she said, had a tremendous “platform”, one that spoke to Asian Americans, and on it, he had posted the equivalent of what would have been a Hitler Youth poster for white people. It was jarring, but the fact that Warren didn’t seem to understand why some Asian Americans didn’t find his Red Guard picture funny suggested that he didn’t care about a whole chunk of his readers. They were people who had read his books and used his church planting material. Were they in for a rude awakening that it was only they who cared about him, while he didn’t care that they existed?

The New Testament scholar Sam Tsang took his minor feelings to another level. In 2011, Tsang had spearheaded a campaign in Hong Kong to expose a celebrity attempt to find Noah’s Ark on Mount Ararat as archaeologically problematic. His post pointed out that it wasn’t just “Asian Americans” who were reading Warren and using his stuff. That very week, Saddleback was planting a church in Hong Kong. It had transnational reach across Chinese-speaking worlds. Memorably, Tsang asked Warren, “Has any Red Guard ever raped your mother?” That was not just colorful rhetoric. It was saying that what might be regarded as minor feelings are real and that taken out of an American frame, the concerns being raised about Warren’s post weren’t even from a minority community, but a transnational one.

And then there was me. Writing as Chinglican at Table, I cheekily said that it would not have been funny if I said that Rick was the “Rick” in Rickshaw Rally. In so doing, I referenced another set of minor feelings, what I’m calling in this piece the over 16 years of blogging about orientalism in evangelicalism (in 2013, it would have been eight years). “Rickshaw Rally” was a reference to the 2004 Vacation Bible School curriculum parodying Asians as rickshaw drivers and other orientalist stereotypes. It prompted then-Cambridge Community Fellowship Church’s Soong Chan Rah and the Angry Asian Man Phil Yu himself to start a website called “Reconsidering Rickshaw Rally” to contest. In full disclosure, I am no longer “Chinglican”. I retired the name like the Dread Pirate Roberts in "The Princess Bride" in 2016 when I became Eastern Catholic, and someone else who is not me uses it now for theologies with which I do not resonate.

Of course, our writing about our minor feelings produced major feelings in the world of Asian American evangelicalism. Grace Hsiao Hanford of AsianAmericanChristian.org logged a bunch of stuff on her Tumblr about how our writing wasn’t actually representative of all Asian American evangelical voices. Some people, for example, felt that we were too confrontational. Some even quoted Matthew 18 to tell us to confront Rick Warren in private instead of hanging out our dirty laundry with him for all to see. This furor reached the ears of Religion News Service’s Sarah Pulliam Bailey, who interviewed some of us. I told her that, despite the objections, “What starts public stays public.” But the point is that that was just one feeling in a sea of minor feelings.

And then, three weeks later, a second orientalist thing that happened at Saddleback. The first Korean American woman to be ordained in the Episcopal Church, the Rev. Christine Lee, was at Saddleback attending a church planting conference hosted by the organization Exponential. They had a "Karate Kid" sequence in their programming, and when she raised her objections to it to organizers, she was blown off. And so, Christine Lee took to Facebook to say that she might have experienced her own “Kathy Khang moment” which led the actual Kathy Khang and Helen Lee of "Christianity Today’s" classic piece on the Asian American evangelical second generation, “Silent Exodus”, to draft an “open letter to the evangelical church” from Asian Americans. Over a thousand people ended up signing it. But Suey Park of the #CancelColbert and #NotYourAsianSidekick sagas, along with the collective she cofounded called the Killjoy Prophets, didn’t like it. Coming from yet another angle in Asian American evangelical politics, she said its sensibilities were too “model minority”, maybe even inherently anti-Black. (And then, because most people ask at this point in the story what’s happened to her now, she’s vanished without a trace; all the gossip is available in Yasmin Nair’s write-up.) Helen Lee wrote another piece in "Christianity Today" in 2015. It was titled “Silent No More”. Truly, I felt as I read it, it was a real cacophony.

That is the thing, though, about minor feelings. Khang, Tsang, and I were different enough from each other, coming at Warren from within our own Asian American evangelical communities. We ended up agreeing on more than we disagreed, but as more voices joined the fray, it became clear that there was not one way to feel as Asian American evangelicals. There were too many communities, too many ideologies, too many different ways of understanding confrontation, whether a Christian should do it, and how to do it.

But the interesting thing is that there was a unifying factor all of this cacophony, too. We all had some (mostly imaginary) relationship with Rick Warren and Saddleback. Whether we read him, used his stuff, admired him, resented him, loathed him, ignored him, or whatever, no one had to explain to another Asian American evangelical who he was, why he was important, what "The Purpose-Driven Life" was about, or even why the church is called “Saddleback” (and that last thing is definitely Southern California esoterica). That was taken for granted, as was the fact that things had happened at his church that could be construed as orientalizing racism. The question was never why he was important or whether anything happened. We splintered on what to do about it.

That’s what Hong’s “minor feelings” are about. As someone who is not white, I wouldn’t pretend to know what Warren’s perspective is — or for that matter, what the authors of the “Rickshaw Rally” curriculum or "Deadly Viper Character Assassination Squad" were thinking. But what I do see as consistent through all of it is that, to parody Ben Shapiro, major feelings don’t care about your minor feelings. The major feelings here would be the tradition of parodying Asians in white American popular culture. If you want the scholarship on this, you can read Bob Lee’s classic "Orientals: Asian Americans in Popular Culture", and if you want to have some fun, you can try Frank Chin’s "Gunga Din Highway", too.

There’s nothing “evangelical” about these white evangelical imaginaries, at least in the sense that they have nothing to do with Jesus, the Bible, or God. They’re tropes borrowed from film noir, Tarantino movies, "Karate Kid’s" reincarnation on Netflix as "Cobra-Kai", and souvenir photo books of propaganda posters you might have on the coffee table to impress your friends at a dinner party. Those are the sources of the major feelings, and as much as I might enjoy a noir flick (or as sincerely as Bong Joon Ho put his hand on his heart at the Oscars and said, “Quentin, I love you”), they make no space for the minor feelings that come out of the cacophony of Asian American evangelical worlds. As the immortal last line of Roman Polanski’s "Chinatown" (a film about L.A.’s Chinatown with no Chinese people in it) goes, “Forget it, Jake, it’s Chinatown.”

There is a certain heartbreak here, that one of the institutions that is regarded as a pioneer of the grammar of our Asian American evangelical lives is led by people who do not really care that we exist except as funny people until we’re not. Saddleback does it again and again, and Asian American evangelicals keep writing about it online. In fact, this time in 2021, the apology is really poetic. Saddleback, Warren says this time, is committed to being an “All Nations Congregation”. That’s rich. Does that mean that Asian Americans are their own nation when they don’t get his orientalist jokes and make noise online instead? That’s self-determination beyond the Black Panther Party’s wildest dreams. Or perhaps Warren gets something that Asian American evangelicals are loathe to admit. There is a power dynamic to the difference between major and minor feelings, and no amount of explanation on the part of the minority will alter how the majority’s feelings are already structured by a popular culture that may not even be contained by evangelicalism.

There is a way, I reflect, where the open letter of 2013 and the writing I find on the AACC now tries to overcome the problem of making the majority care about our minor feelings by explaining to them why orientalizing practices are wrong. There is an assumption that their readers should care, and do, as fellow Christians, the Body of Christ, a family of believers — or even, as per Warren’s apology, a “Church of All Nations”. But maybe they don’t, because their imaginative world is not ours, and we have never existed as people in theirs anyway.

Besides, if all we try to do is to make people more ideologically powerful than us care that we exist, what might get lost, I feel, is why we care, all of us, in our glorious Asian American evangelical cacophony. I wonder, in other words, if all of that self-published writing needs to be so explanatory about the perils of orientalism in evangelical culture. Really, I feel like if you’re still in denial about white supremacy in 2021, what you probably need is not an explanation, but an exorcism.

So what if, say, we wrote candidly about the words and diagrams that have shaped our Christian lives since our childhood, even if it makes us cringe as much as memories of our college music might? That would probably look different from the open letters and online explainers that really seem to have dominated the output of Asian American evangelical online protest for the last 16 years. It might even get messy, exposing just how entangled we as Asian American evangelicals are with the publication networks of white evangelicalism. I suppose that might make some people nervous. It might undermine, for example, the multiple attempts over the years to cast “Asian American Christianity” as its own thing. And yet, that is the point of minor feelings. We do appropriate from popular culture, we try to make it our own, and we disagree with each other on how to put it all together. Writing in a way that embraces the cringe of all those attempts would thus be no less noisy than all the times we wrote about why the orientalizing at Saddleback is bad and made fellow Asian American evangelicals all kinds of nervous. In fact, it would still be blogging and online self-publishing, and after over 16 years of doing that, really, why stop now?

Justin Tse (he/him/his) is Assistant Professor of Humanities (Education) at Singapore Management University. He is the lead editor of "Theological Reflections on the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement" (Palgrave, 2016) and is working on a book manuscript titled "The Secular in a Sheet of Scattered Sand: Cantonese Protestants and Pacific Secularities" (in preliminary agreement, University of Notre Dame Press). Although he is Eastern Catholic, he cannot seem to stop writing about Asian American evangelicals. Also, he is happily married now. He stopped using evangelical pickup lines.