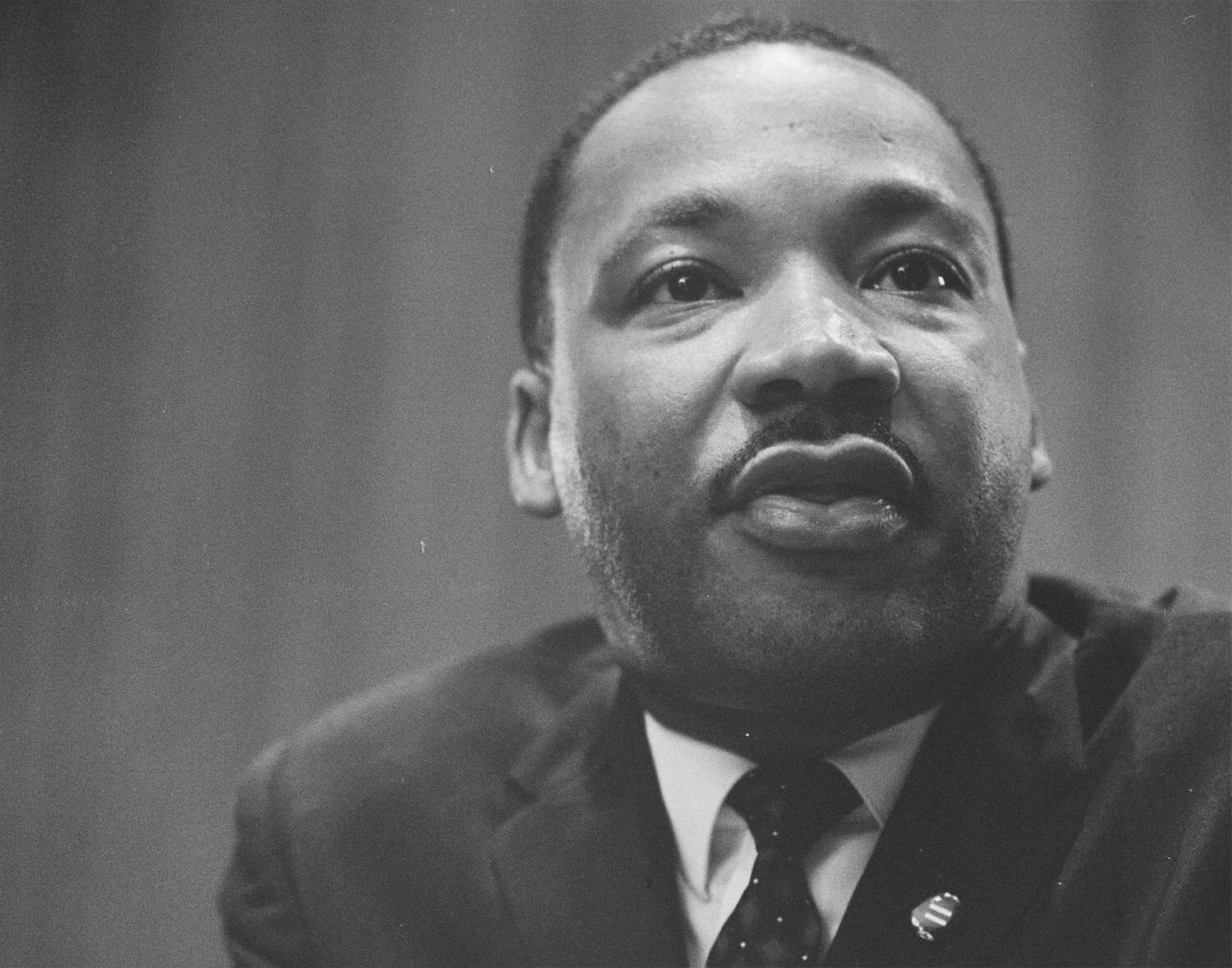

My students call me a Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. scholar; I published two books and wrote a number of articles on Dr. King, and am currently serving as co-chair of the Theology of Martin Luther King, Jr. Unit at the American Academy of Religion, the largest guild of religious scholars in the world. Some may wonder how an Asian American can have the audacity to identify himself as a King scholar. What does King have to do with Asian American identity? These questions are understandable, given that King was an African American and I am a Korean American. Without sharing the same ethnic membership and unique historical experiences of African Americans, how could an outsider be an expert on King?

I humbly accept these reactions. In this reflection, I respond to these questions by providing some reasons that I chose to undertake the scholarship of King. My interest in King is not purely academic, but spiritual and existential. King helped me to integrate and deepen diverse facets of my identity as a Korean American Christian. I’ll start with some personal background before sharing my more systematic interface with King.

My exposure to King goes back several decades. King was one of the moral exemplars that Korean Christians looked up to during a democratic movement against the military dictatorship during the 1970s and 1980s. Most Koreans of my generation remember singing together “We Shall Overcome” in Korean on our campuses, in the midst of dense tear gas clouds and flying rocks. King’s vision and method partly helped to bring about the peaceful transition of South Korea to a democratic society.

During my doctoral study at Princeton, I was involved in African American and Asian American dialogues at practical and intellectual levels. In the wake of the African American and Asian American conflicts in the late 1980s through the early 1990s, including the L.A. Riots, I was involved in an intercultural ministry in the Camden, New Jersey area for six years, out of concern for African American and Korean American racial harmony. Through that experience, I found that America is a complex cultural and political entity — morally incoherent and spiritually schizophrenic. In its idealism and political vision, America claims to be inclusive, but in its cultural and racial history, it has been savagely exclusive and violent. It is made up of diverse immigrants from all over the world, but racism still abounds in many different forms. I also learned that we need a capacious theological paradigm that takes both the identity of each group and their common goal seriously. As James Cone emphasized, race has never been a serious intellectual, moral concern for white theologians. While America is highly racialized — with racial identity as a primer of one’s social identity — white theologians and pastors typically ignore and avoid this issue, out of guilt, shame, or arrogance.

Upon the completion of my doctoral degree from Princeton Theological Seminary, I prayed that God would help me find a good role model for my vocational calling. I didn’t want to simply be confined to the ivory tower, publishing books (although it is also important), nor did I want to piously care only for my own spiritual wellbeing and a local church’s. As a Christian ethicist, I wanted to serve Asian American churches in a way that would be spiritually vibrant, theologically faithful, and socially transformative. In the process of rigorous prayer and meditation, it was revealed to me that King is an excellent Christian role model in integrating multifaceted aspects of my identity: He was an African American, a Christian, a pastor, a scholar, and an activist.With the exception of not being an African American, I share the other named facets of King’s identity. I am a Christian, an American, a pastor, a scholar, and an activist.

As a Christian, I am inspired by King’s dialectical, balanced, and theologically faithful posture toward identity. While quintessentially African American, King was also engaged beyond the African American community. King was a Christian who took racism and racial identity seriously while constantly laboring to transfigure it in the context of his identity as a follower of Jesus. This spiritual effort, which started in his student years, bore the fruit through his public ministry. While being a Black Baptist preacher, King was a model of Christian commitment and of dedication to God and humanity. He was not only an iconic symbol of African American Christianity, but also a global moral leader and exemplar respected by people of various religious, cultural, and national backgrounds.

To no lesser degree, King’s global influence had to do with his ability to incorporate his African American identity into his Christian identity in the manner that Jesus’ human identity was united to his divine identity. Patristic Christological languages, an-hypostasis and en-hypostasis, explain how the union of humanity and divinity happened in the enfleshed person of Jesus Christ. By en-hypostasis, it is said that Jesus did possess the real human nature, but that his human nature could not stand alone (thus an-hypostasis); it is engrafted in his divine nature. In other words, while assuming human flesh, Jesus did not abandon his divine nature; rather, it is incorporated into his pre-existing divine nature. While both identities are important, they are asymmetrically integrated to the side of his divinity. This union of two identities in Jesus has profound implications for Christians to think of their identities. That is, true Christian identity is grounded in history — its cultural and racial and gender particularity (en-hypostasis), while not completely reducible to it (an-hypostasis). It is anchored in the imago dei of each person restored by Jesus Christ.

King also exemplifies this form of asymmetric identity: He celebrated his racial identity under the rubric of and in the context of his Christian identity. Even under the pressure from the Black Power movement and Malcolm X (who once disparaged King as “Uncle Tom”), he never compromised his stance on the equal sanctity and universal solidarity of humanity. Similarly, when he was harshly criticized by the U.S. mainstream media for his protest against the Vietnam War, King boldly justified his involvement in the peace movement by reminding them of his primary identity and calling as a disciple of Jesus.

Through studying King, I found that my identity is a racialized identity. Even my Christian identity cannot override or delete it. It constitutes a crucial part of who I am in this country; it also cannot be detached from racialized identities of other groups in American history. At the same time, this racialized identity is not the most definitive one either. The center anchor of my identity is Jesus Christ, and all other aspects are secondary; the former is eternal while others are historical and temporary.

King’s example offers a creative, authentic framework that I can rely on to navigate the increasing clash between secular postmodern politics (liberationist) and conservative evangelical approaches to racial identity. That is, King offers a third way between overzealous, sometimes divisive identity politics and a-cultural, a-racialized or post-racial evangelical identity.

In general, identity politics refers to political ideologies and activities that are based on the aspects of a person’s identity such as sex, gender, race, ethnicity, age, disability, and so on. It attempts to reclaim one’s own sense of identity, agency, and community free from negative social scripts, oppression, and ostracism against its identity. However, when essentialized, identity politics may build new barriers and even increase alienation and enmity between groups, because essentialized identity politics operates out of a monolithic binary logic — the oppressors vs. the oppressed — at the disregard of intersectionality with other identities.

On the other hand, in their life journey in the U.S., most Asian American evangelical Christians seldom discuss their racial identity. Asian American Christians take white theologians and pastors as their primary role models in every aspect of their ministry and spirituality. They adopt the post-racial approach of white evangelicals. They think that racism is not a major concern; it can be overcome by merits and good work ethics. They point to English fluency and educational and economic success as examples, although Asian Americans have been consistently discriminated against and dismissed in U.S. history. This stance is morally irresponsible, spiritually deficient, and culturally un-authentic; it cannot bear good fruit. Active Asian American political voices are long overdue given the rampant bullying, social stereotypes (e.g., “model minority”, “forever foreigner”), and marginalization (e.g., the Japanese Incarceration, the 1992 L.A. Riots) of Asian American communities.

Asian Americans still face the huge task of exploring Asian American identity in its complexity and plurality, of exploring conversation with rich Asiatic religious cultural traditions, and of measuring and arranging our relationships with other racial groups. However, finding a right posture is a critical first step in this search, and in this aspect, King’s example is inspiring and instructive.

King is an exemplar of how we can celebrate our cultural racial identity without suppressing our Christian identity or our common quest for God’s Kingdom — the “beloved community” in his phrase. King’s approach is not only theologically faithful but also politically effective because one racial group alone cannot dismantle systematic racism without the collaboration of other races, including whites. Furthermore, in a globalizing world, creating a community has become a moral mandate, because ongoing competition threatens the future wellbeing of our entire humanity and the planet.

This means that the destiny of humanity is tied together, and each group needs to think about its own identity and politics in light of the common good, asking: What kind of society do we want to create together and what could our contribution be? Such a form of racial identity is similar to jazz music. Like King who also originated from the African American community, jazz is now globalized. Jazz is distinctive from other genres of music because of its emphasis on improvisation. While sharing the same note, it gives each performer or player ample space to be themselves — to freely express their emotions in their own sound and style while spontaneously listening and responding to one another.

From King, I learned that the Asian American community is one of those jazz players in God’s cosmic band performing our splendid song attuned to a rhythm of the Triune God, while calling and responding to other members until divine glory fills every life and every corner of this planet.

In this sense, King was not only a good African American brother, but also a God-sent teacher to me. He helped me to find my Asian American voice to serve God’s beloved community.

Hak Joon Lee is Lewis B. Smedes Professor of Christian Ethics at Fuller Theological Seminary. Lee has published several books, including “Intersecting Realities: Race, Identity, and Culture in the Spiritual-Moral Life of Young Asians” (edited, Cascade Books), “The Great World House: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Global Ethics” (Pilgrim Press, 2011), as well as numerous articles. He is currently working on two manuscripts under contract: “Discerning Ethics: Diverse Responses to Divisive Social Issues” (coedited with Tim Dearborn, IVP Academics), and “New Covenant Ethics: Methodology and Practice” (Eerdmans). Additionally, in 2007, Lee founded G2G Christian Education Center, a research institute on Asian American Christianity and culture. Through the Center, he has published several contextually grounded curricula for Korean North American youth (English) and their parents (Korean).