I had done my fair share of activism in college and post-graduation, but never quite long enough to see actual change on an institutional level. On paper, JoAnne Kagiwada had an impressive roster that placed her in the history books, and I was readying myself to meet a force of nature in this small-framed, Japanese American grandmother.

In activist communities, leaders are often called organizers because building movements takes a lot of time, education, and intense energy to assemble people to act. Chances are that they’re leaders borne of fire — from the ashes of tragic personal circumstances and a constant testing of one’s political and social analyses. Burnout is a common occurrence.

Yet, none of these factors seemed to apply to JoAnne and her work. In many bewildering ways, it was less organization and more happenstance. “My grand plan was ‘Oh, that looks like fun, I think I want to do it.’ And then there was the steep learning curve. I’ve done badly at more jobs than some people have ever had,” says JoAnne.

Back in the 1980s, what apparently looked like fun to JoAnne was holding Congress to its word in what was promised in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, the official public apology from the United States government for the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The Act committed to creating a public education fund to prevent future recurrence and distributing $20,000 to each eligible individual who had been incarcerated, including the native Aleut residents of the Pribilof and Aleutian Islands.*

The Act itself was government authorization in words alone; what has often been overlooked was the subsequent work to get Congress to follow through and appropriate the promised funding. At the time, it seemed like a hopeless undertaking to find support in Congress for a wrongdoing that happened 40 years ago. But in a bold move, Senator Dan Inouye from Hawaii persuaded his colleagues to amend the Balanced Budget Act and create redress as an additional, completely funded entitlement program not dependent on leftover discretionary money.

JoAnne conducted grassroots lobbying on behalf of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) to get the states to support the redress bill. Tapping into her networks with the Disciples of Christ, the National Council of Churches, other faith groups, and civil liberties organizations, she worked closely with Sen. Inouye’s office to garner votes from the many states across the country where there were few Japanese Americans.

“The financial payment was a critical element in the redress process. It was in no way understood to be compensation. An apology wouldn’t have been as meaningful unless there was some financial attachment, so people accepted it for what it was,” says JoAnne.

Unexpectedly, the long journey to gain redress and reparations faced some resistance from among Japanese Americans. In 1980, the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians had been established to conduct hearings across the country, collecting first-hand accounts of what Japanese American citizens experienced in camp as a foundation for drafting the Act. That process was hampered by a strong reluctance in the community to remember what had happened.

“I think the parents thought, ‘Maybe if we don’t talk about it, maybe it didn’t really happen,’” says JoAnne. “Gaining redress took the kids of those families who studied a little bit in school, came home, and asked if they went to camp. The third-generation or Sansei was growing up in the Civil Rights Movement and they discovered that they had their own civil rights that had been violated. Because time marches on, there were more ‘youngsters’ working on redress than those who had been sent into the concentration camps.”

Though most of her peers are second-generation or Nisei, JoAnne is of this Sansei generation.

JoAnne was 5 years old when her family packed their bags for a life in a U.S. concentration camp. But as luck would have it, her family never had to go. When the notice for individuals of Japanese descent to vacate the West Coast was posted in their town, her father petitioned the military for permission to move to Minnesota, where her uncle lived. The travel authorization arrived on July 4, 1942.

While all her Japanese American friends and neighbors were relocated to assembly centers, her family of nine huddled into three cars for the Midwest. Her family’s home and chicken hatchery business were left to the trust of the Vogt family, Russian-German friends who guarded and cared for the property until they returned.

Her family arrived in Mankato, Minnesota, a predominantly German and Scandinavian community. JoAnne recalls, “My dad said that the Germans remembered what had happened to them in World War I, when they were treated as badly as we were in World War II. We were accepted, the only Japanese kids in town, so I don’t remember any bad incidents at all.”

Let that sink in a bit. JoAnne didn’t have a personal investment with redress and reparations. She had lived in times that demanded action, and she simply said yes. This deep value for resistance to injustice reflects her parents’ teaching, especially from her father, who was active in the JACL since its founding in 1929.

“It wasn’t that I reached out and grabbed it as a cause that I needed to be involved in. It was just so terribly wrong!” says JoAnne.

“When things are not as they should be, the gut feeling that comes to me is this is wrong and I should try to do something to make it right. That doesn’t always get expressed in big, outward things, but that always is my sense of justice. God created the world to be good. What I’m supposed to do is help things be good. Faith and justice fit together: What is right, what is just, what do I do because God loves me and loves all of God’s children?”

JoAnne’s life is a testament to what powerful change can happen when a person sincerely tries to answer this question. Can social change truly be that simple, if enough people believe as she does?

The majority of activism is arguably to get people to care — to see one’s humanity tied to the humanity of another, whether it’s a corporate executive or a garment worker. That work alone is so taxing because there aren’t more people saying yes to collective struggle. Some people may dedicate themselves to justice work because they are oppressed — the story of their life demanding no other recourse — but JoAnne dedicated herself to this difficult work while uniquely privileged, without major trauma from incarceration.

That isn’t to say her journey has been all easy. JoAnne shared about her previous international work experience with the Disciples of Christ. At the height of the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, when mutually assured nuclear destruction was a very real fear, the Soviet churches convened an international conference attended by over 600 people from 90 countries around the world to speak out against the Cold War and send a message to their respective governments. The conference title is a mouthful: The World Conference of Religious Workers for Saving the Sacred Gift of Life from Nuclear Catastrophe.

JoAnne attended as a delegate representing the National Council of Churches (an ecumenical organization that the Disciples of Christ is a member of); she was the only Asian American and only woman plenary speaker, sharing the story of Sadako and the thousand paper cranes to illustrate the imperative for world peace.

“I was in an arena of work and relationships that was mostly white and male. I had to be smarter, better, faster. Not as fast; faster. I had more wariness about appearing not strong and I wish I could’ve just let my vulnerability be a part of who I was. But sexism works two ways: Whenever you needed someone to do a panel or a representative, I was a lay person, a woman, and a person of color — a three-fer,” says JoAnne.

JoAnne was committed to her work with all its challenges, but her path to this position of influence is astounding. It begins with her kids wanting her out of the house. JoAnne has three children with her late husband David Kagiwada, a pastor with the Disciples of Christ.

“When the youngest one started going to school, my kids came home, they lined up with their hands on their hips like this, and said to me, ‘Why don’t you go to work like everyone else’s mother does?’ I was a very managing type,” she says with a smirk.

She took the LSAT for fun, and before she could determine if she wanted to become a lawyer, her husband resigned so she could go to law school at University of California, Berkeley. It was there that she became involved in international human rights law.

“That pioneer area of law appealed to my sense of justice, and I thought it was fun because it meant that I got to go to Geneva on school time. Senegal. New York. But the regular law school classes were not fun.”

Her international experience opened the door for her to become Director of International Affairs with the Disciples of Christ, in charge of education and interpretation of global issues and how the church can be involved, and ultimately, to her flying to Moscow for the conference.

Again, it wasn’t a personal connection to nuclear war or a fervent concern for international relations that motivated her in her illustrious career. JoAnne says, “My sense is that to be a token is not a bad thing; it gave me opportunities I might not have had. My goal was to be good at what I did. If you got the opportunity, you better deliver.”

Throughout her journey, JoAnne had several choices to do something easier with her life, but didn’t — a true steward of the access she’s been given. It is frustrating and at the same time hopeful to think that if there were more JoAnnes in the world, perhaps our movements would be stronger.

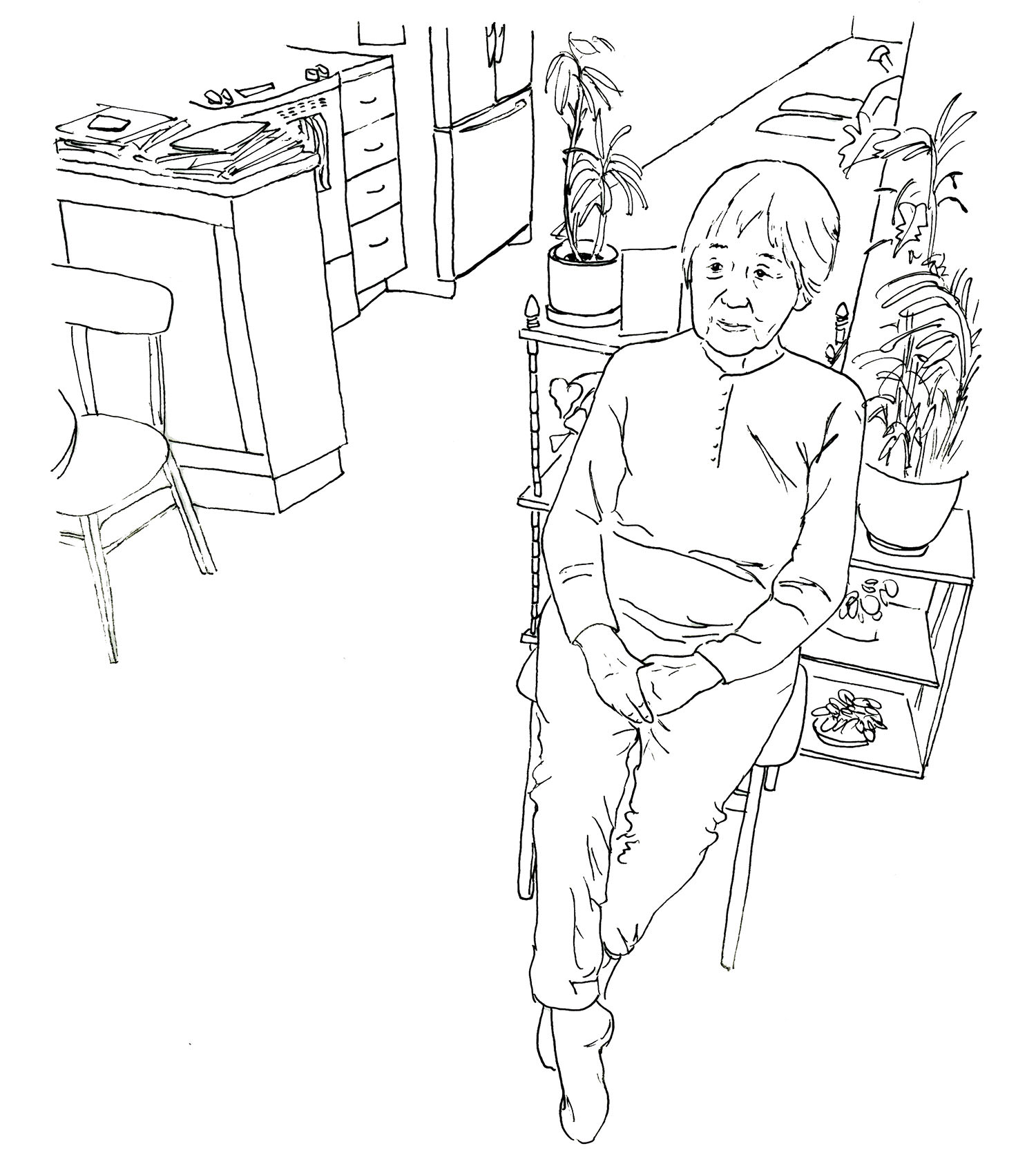

Today, she is 80 years old. JoAnne is involved in very different platforms than she’s used to, but her values remain as constant as ever as she volunteers regularly with the Oakland Peace Center and is an active member of the Buena Vista United Methodist Church. She pulls out an old manila folder and shows me clippings of her from newspapers and articles she’s written; one paper depicts a much younger JoAnne in a black and white photo, looking smart in a business suit, and her quote on the frayed page is impassioned and visionary. I wonder if time has softened her memory of her past or if what you see is truly what you get with JoAnne.

JoAnne says, “I was proud to be a part of making redress a reality. But again, it wasn’t because I was leading the way. A lot of it is luck, but luck is also to take the opportunity when it’s offered. Because if you don’t say OK, then that’s something that will never happen. I don’t have any of those big things that say, ‘Oh, this really brought world peace’ or ‘I was the very first to do something.’ I’m not very interesting.”

Her eyes twinkle as I burst out laughing. For she is the most interesting not-interesting person I’ve ever met. It turns out, to become a part of social change, you don’t always have to begin with critical race theory or bear a traumatic connection to injustice. Say yes — that’s a good place to start.

* In a separate section of the 1988 Civil Liberties Act the Aleuts' individual payments were $5000 with a larger amount establishing an educational foundation. The Canadian government also enacted their own redress program with different provisions, following the lead of the U.S. However, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was not comprehensive: It did not include heirs of those incarcerated who had died before the Act was signed. Also, some 3,000 people whose country of origin was one of the enemy axis countries were abducted from Latin America and interned in the U.S. for possible exchange for American citizens trapped in enemy-controlled territories when the war broke out. About 2,000 of them were Japanese, mostly from Peru. Unwilling immigrants, they were never given legal status and therefore were not eligible redress recipients. The struggle to correct that wrong has still not been resolved.

** In the story, Sadako, sick from the effects of a nuclear bomb, hopes to fold a thousand paper cranes to make her well, but she dies before she can finish. Her friends and family fold the remaining cranes and bury them with her.

Sarah D. Park (she/her) is a second generation Korean American born in Los Angeles, CA. Her work reflects her value for finding abundance in community and the power of telling our own stories. She’s currently based in NYC and spends her time eating cheeseburgers, creating community spaces, and enjoying her son.

Caren King Choi is an artist, writer, and nonstop doodler from New Jersey. She studied art and writing at Colgate University and works as the Associate Director of Programs at Rutgers University-Newark. She and her husband live in a one-bedroom apartment that is steadily being overrun by books (hers) and guitars (his).