I stood on the sidewalk outside of Circle K in awe. It was 11 p.m. on a Sunday. Soft streetlights cascaded down onto an uproarious crowd full of people, young and old, standing shoulder to shoulder on the vehicle-less thoroughfare. It was a rare sight to see in one of the busiest parts of Hong Kong.

A man in his early 20s swung from a lamp pole, speaking emphatically into a bullhorn. The number of onlookers below him swelled. I was completely surrounded.

I may have looked like any other girl there but there were only two words I understood: gaa yau!

“Gaa yau!” he yelled, raising a clenched fist while clutching onto a street pole.

“Gaa yau!” the crowd screamed back.

Add oil! Just like that, the Umbrella Movement had just begun for me.

Nearly three years ago I moved to vibrant, bustling Hong Kong from sunny, laid-back California. All the things I took for granted in the States were illuminated to me in Hong Kong. The bountiful amount of space. Clean air. Taco Bell. Dry weather. No cockroaches. Did I mention space?

But for the most part, I found life in Hong Kong to be what existing must be like in any major metropolis — fast-paced, hectic, unforgiving and pretty damn exciting. To my surprise, even close Chinese American relatives would often ask me, “How’s China? Do they censor you from going on Facebook or Gmail?”

Hong Kong is about as free as a Chinese society can be. In fact, referring to Hong Kong as “China” has always been a bit insulting, even to me, a very removed ABC girl who can barely speak elementary Cantonese. Yes, we can go on Facebook, Gmail, and Twitter without a Virtual Private Network (VPN). No, we do not have to kowtow to Mao.

There were plenty of evangelical churches to attend on Sundays and actually I had my pick of the litter in terms of diverse, English-speaking Christian churches. I have so many English-speaking North American friends, sometimes it’s almost like living back in the Bay Area.

But the pervasive influence of Beijing was clearly seeping into the very foundation of this Special Administrative Region. In my short time here, numerous news broadcasts were indicative of these changes: parents protested against pro-Communist curriculum being integrated into their children’s schools; outbursts between touring Mainlanders and local Hong Kongers flared up here and there; news articles chronicled the demise of Cantonese or worse yet, demonized the dialect for not being, well, Mandarin. Almost three years in and I couldn’t deny the visible onslaught of Mainland tourists pouring into the city’s shopping centers, or the sound of Putonghua, the official language of China, now on nearly every sidewalk.

According to the South China Morning Post (see their October 9, 2014 article “How Occupy Central’s Democracy Push Turned Into An Umbrella Revolution”), the Umbrella Movement began as Occupy Central — Central being the financial center of Hong Kong — as a civil disobedience movement that called on protesters to block roads and essentially paralyze the financial district if the Beijing and Hong Kong governments did not agree to implement universal suffrage for the chief executive election in 2017 and the Legislative Council elections in 2020 according to “international standards”.

The media picked up on the movement relatively late, saying the movement began in September 2014. In truth, the movement began as early as 2012 when 18-year-old student leader Joshua Chi-fung Wong led public sit-ins to protest Communist education reforms in Hong Kong. Wong, who was raised by Christian parents, has said the ideographs for his Chinese name, Chi-fung, means “sharp spear”, which his parents chose as a reference to Psalm 45:5 — “Let your sharp arrows pierce the hearts of the king’s enemies”.

At 14, Wong, founded Scholarism, a group of secondary school students, to fight a campaign meant to convince the government to drop the “national education” plan, a curriculum with pro-Communist undertones.

Wong’s campaign was successful and he was able to rally an even larger populace — counting up to 90,000 on some days — four years later, in 2014, when Scholarism joined forces with another student group to form the Umbrella Movement.

In 2014, the visible fight for democracy mushroomed beyond student meetings, and Joshua Wong was making headlines again. I remember headlines in July about these student meetings were just surfacing when they reached 200 attendees — it was clear this movement was sprouting into something momentous. The media’s interest was clearly piqued and civil engagement was stoked almost immediately.

For Wong, defending democracy is about human rights and human dignity. Wong has openly stated, “I believe in Christ. I believe everyone is born equal and loved by Jesus.”

But for Beijing, this perspective is fundamentally opposed to Communism. Man is not made in the image of God. Rather, “Man is made for the state, not the state for man.” As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote of Communism in his book, “Strength to Love”:

“All of this is contrary, not only to the Christian doctrine of God, but also to the Christian estimate of man. Christianity insists that man is an end because he is a child of God, made in God’s image. Man is more than a producing animal guided by economic forces; he is a being of spirit, crowned with glory and honor, endowed with the gift of freedom. The ultimate weakness of Communism is that it robs man of that quality which makes him man.”

In the humanistic lens of Communism, autonomy reigns supreme and people are a means to an end. God has no place because man needs no saving — man can save himself.

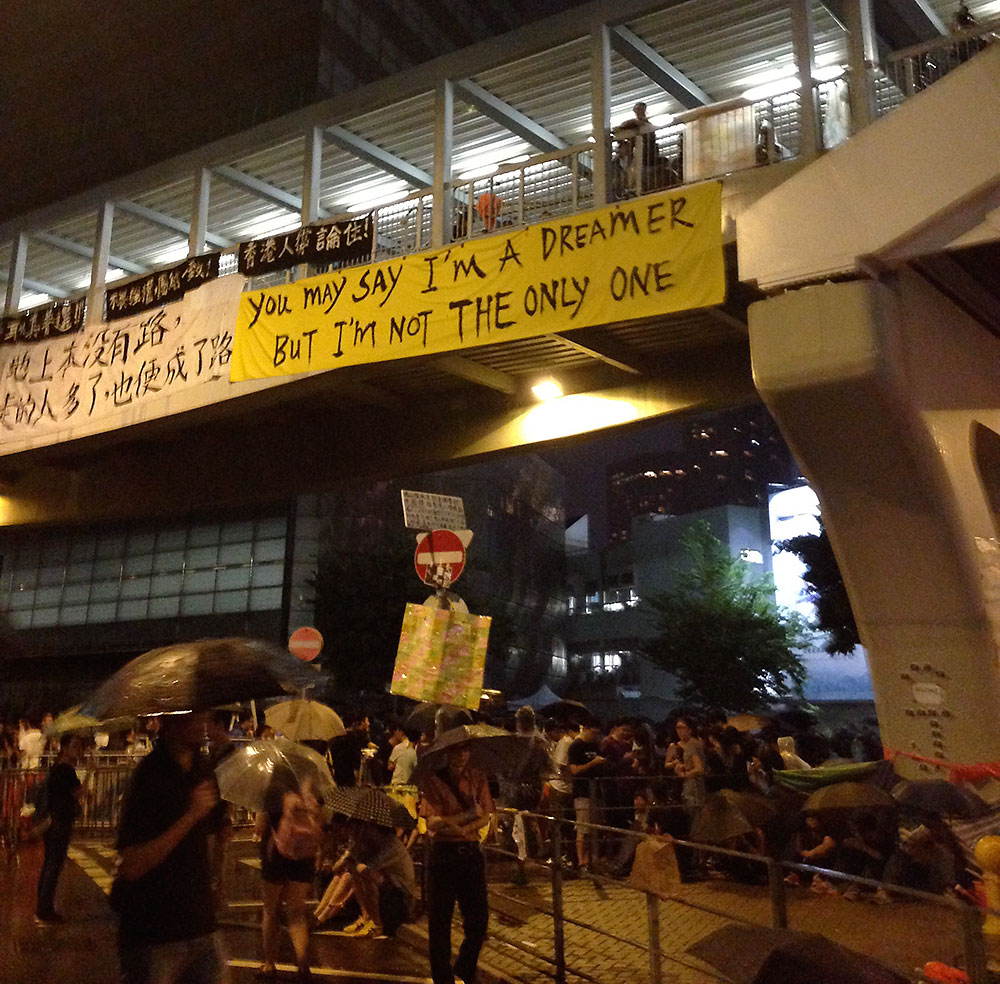

By September, Hong Kong’s landscape was upended. Protesters numbered 100,000 at any given moment, blockading major roads with tents, makeshift beds, lawn chairs, and supply stations stocked with crackers and donated food. Bus routes were immobilized due to the growing number of highway encampments, leaving the subway overwhelmed with an influx of daily commuters. The large highway outside my apartment was now ground zero for the Umbrella Movement.

Strangely, life remained relatively normal even though Hong Kong’s chaos was in the news every night. The city known for its world-class public transit, orderliness and efficiency was now reeling with footage of police throwing tear gas, students hovering behind umbrellas and people screaming at each other. Images of chaos and hostility were everywhere — but it was almost as if the quietness of Hong Kong actually spelled utter chaos simply because this wasn’t how things were meant to be. The quietness represented the division Hong Kong and Beijing; between Hong Kongers and police officers; between generation Y, who didn’t know a thing about making money or supporting a family and generation X, tired of the diverted bus routes, tents, and Hong Kong making nightly news for chucking tear gas at its citizens.

I felt deeply for what was going on and was scared. It was common to see cynical commenters on Facebook say things like “Hong Kong is just becoming another Chinese city”. But it didn’t seem like anyone actually wanted that. I didn’t want the vibrancy of Hong Kong’s blended heritage to die out under the relentless weight of Communism. Of course, as an American, I wanted Hong Kongers to have a say in their future, to know their intrinsic worth and their value as individual human beings.

Yet, I couldn’t understand almost any of the speaking or shouting going on around me. Or the nightly TVB news broadcasts. Or the Chinese newspapers.

When I had time during the day, I’d go out to the protest areas and just sit there with everyone. It was usually blazing hot but that didn’t stop anyone. Kids would hand out cold towels, asking if anyone needed one. Stations were set up with free food. Volunteers offered water, even massages. There was always a crew of young men to help people step over the highway barricades.

The more I was out, the more I got the sense that this was a microcosm of the church. Everyone was in the streets, but there was an unprecedented level of generosity, conscientiousness, kindness, and compassion. Rather than the frenetic rushing from one place to another, as was the usual for Hong Kong, people were taking care of one another, ensuring each other’s safety and placing the regard for all people over the individual.

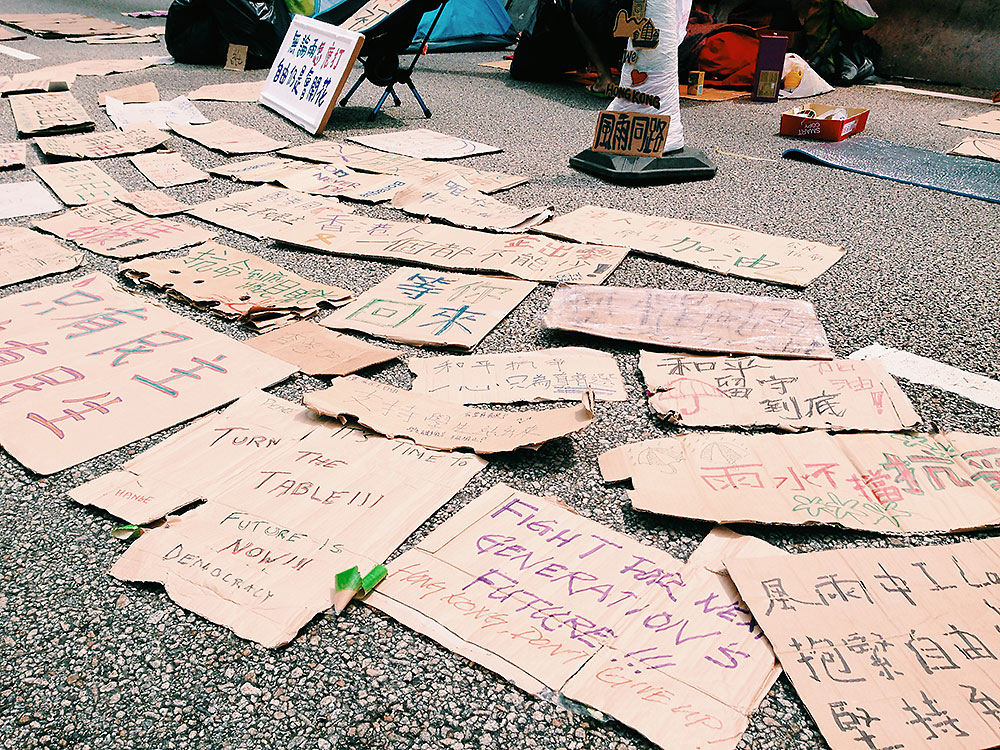

The protest areas had a lot of artwork and signs. The ones in English largely referenced language from the U.S.’s own Civil Rights Movement:

“Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

There was an outpouring of global support from people around the world. Visiting tourists were often seen snapping photos of the tent-filled roads and international news crews were there day and night. Many signs were written in other languages — Swiss, German, French, Italian, and Spanish. On Facebook, it was common to see friends in Hong Kong post photos of groups that were meeting in solidarity of the Umbrella Movement in Paris, San Francisco, Melbourne, Los Angeles, New York, Toronto, and Sydney.

There was something familiar about it — it felt like a mix of being back in college, with how close and communal everything felt; spending a night at church with the youth group, serving one another; sitting in one of my history classes, learning about Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Civil Rights movement. But there was also something very foreign about it.

I’d wonder, “Is this the way the church is supposed to be? You’re at home, but at the same time, you’re not?”

I certainly felt at ease with the displays of peaceful protest, with the idea of fighting for universal suffrage and democracy — but in a place that wasn’t my actual home, among people whom I didn’t know and couldn’t communicate with. The fight wasn’t actually my own and yet I cared so much about it.

The encampments were completely cleared out by December and life eventually went back to normal. There are still signs of the movement all over Hong Kong — yellow ribbons and banners with yellow umbrellas decorate roadsides, street shops, and T-shirts. For many Hong Kongers, the movement has not ended even though the encampments are gone. In March the following year, the showing of Hollywood’s Selma was warmly received across cinemas in Hong Kong with moviegoers resonating deeply with David Oyelowo’s cries for justice and universal suffrage. Later even hip hop artist Common would make a shout to those fighting for democracy in Hong Kong during his Oscar acceptance speech.

My experience with the Umbrella Movement will stay with me forever and my memories of what happened will not fade quickly. I still often wonder what Hong Kong will look like in just five years. Or 10 years. So much has changed even in the short time I’ve been here. I pray and dream for Hong Kong, that it may enjoy a future that demonstrates a hope for the next generation, one that values the lives of its citizens and seeks justice for all. It will be a long road, but I know the city’s fire still burns bright.