Christian theology speaks of the concept of sanctification, the process by which through a life of discipleship and faithfulness we may daily draw closer to the divine, further develop moral character, and deepen our own holiness. The process of canonization, by contrast, is a formal Roman Catholic ecclesiastical decision, through which an individual is posthumously beatified, deemed worthy of worship or at least admiration, and lifted to the status of a sainted soul assured to be in the presence of God.

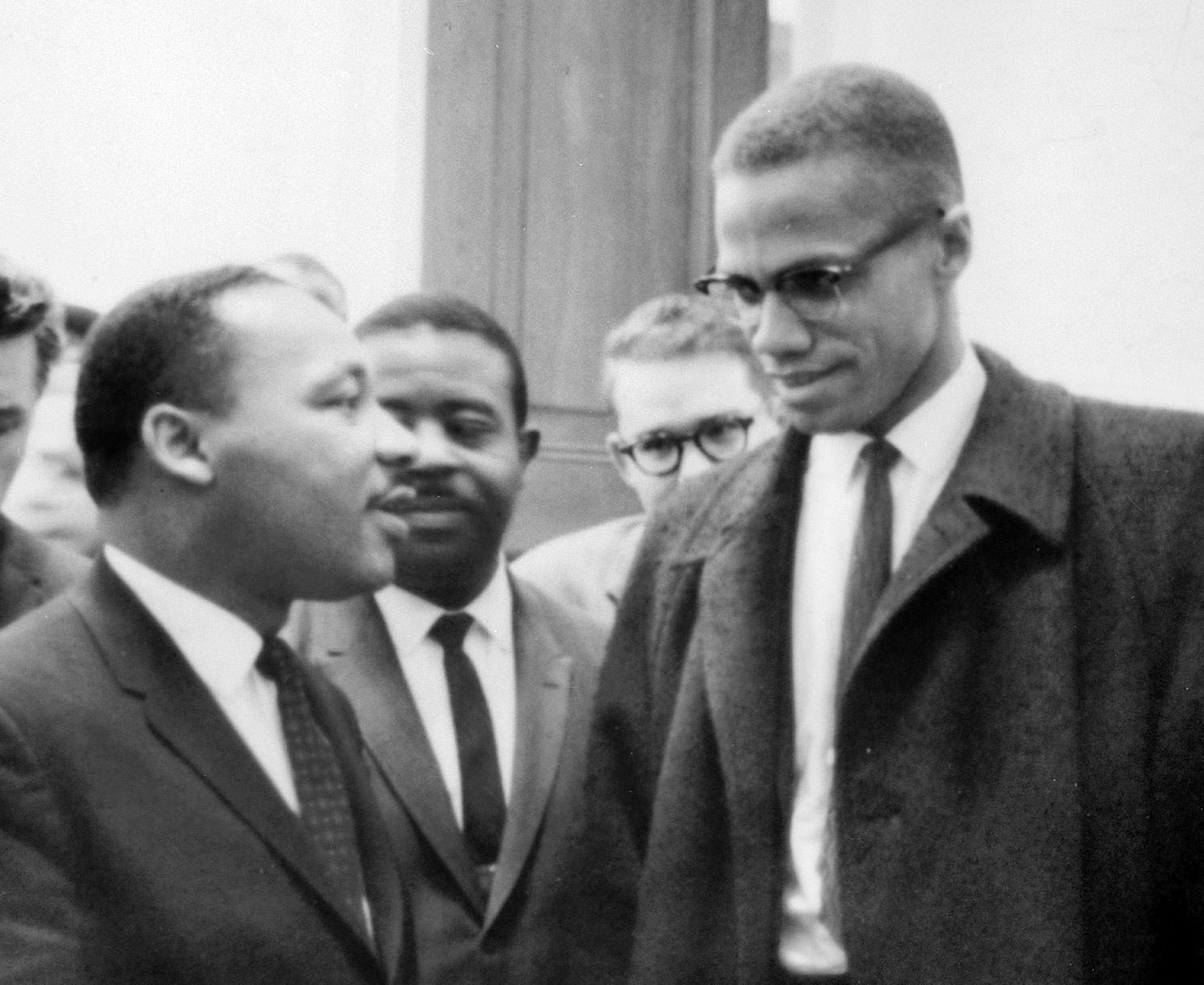

A political iteration of this procedure is illustrated powerfully in the cult of secular sainthood that has arisen around the life and legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr., in the decades since his murder. As artist and scholar Eve Ewing has observed, perhaps no figure in American history has had more projected upon them than Dr. King (by certain markers, even Christ stands a distant second). Martin’s flesh has, quite without his consent, become the living canvas onto which multiple hidden and unformulated parts of our own national identities – political desires, racial anxieties, and unrealized hopes and dreams – have been projected, litigated, and carved out.

King’s deification neatly aligns with Western conceptions of authority and “leadership”, particularly in church and civic settings which uplift one person as singularly salvific or individually monstrous. Even the mononyms and synecdoches we ply in common speech — through entertainment, political, and legal realms — all serve to obscure the complicated relationships which animate these structures; hordes of faceless songwriters, clever producers, light and sound technicians, mentors and security guards, not to mention domestic laborers, food growers, and educators, coalesce their lives and labors into what we know only as “Sting” or “Madonna”. Targets of our disdain, as well as our admiration, are also stripped from their formative contexts, as quotidian complicities go unnamed. We rightfully identify and condemn Trump’s racist constitution, Moynihan’s report, Columbus’ slavecraft, Hitler’s genocidal zeal, and perhaps lose focus on the thousands in their employ whose hands faithfully carried out the commissioned crimes — the lab assistants and captains of industry, droll analysts and middle-managers, map-makers and police officers and cultural creators who, drinking deeply of the doctrines of whiteness, buoyed such pathologies to life on a grand scale.

As Carl Wendell Hines Jr. laments in his poem “a dead man’s dream”, dead radicals make for agreeable heroes: “Now that he is safely dead, let us praise him ... it is easier to build monuments than to build a better world.” Committees and coalitions make for inconvenient statues, and for even more stiff and awkward fuel for cheap political rhetoric. And so Martin King and Rosa Parks, despised in their lifetimes, are posthumously whitened, limbered up, and made representative of the hidden labor of thousands, marshaled to deeply ironic ends. Their unrecognizable faces, now in gleaming marble, lose any hue of struggle and desperation, coolly assuring us that all of this progress was simply inevitable: America is a self-righting ship, an aromatic recipe divinely cured with all the proper ingredients already baked-in, right from the beginning.

The 2nd century theologian Tertullian, observing how state persecution often had the unexpected effect of growing the church, once wrote that “the blood of martyrs is seed”. Indeed, those prophets who have met violent ends often had their words amplified in enduring ways — St. Paul, Anne Frank, Mahatma Gandhi, Sadako Sasaki, Emmett Till, Steve Biko, Che Guevara, and others come to mind. Tertullian’s axiom is likely correct. Yet, it’s also true that we’ve focused far more on the seed of martyrs than we have the soil — the particular climates, native nutrients, and careful conditions by which their growth was culled and cultivated. In uplifting the seed over the soil, we have frequently gorged ourselves upon the most domesticated and saccharine shreds of these figures’ thoughts, and dismissed a more comprehensive, ecological view. As those engaged in social change, might an alternative framing ground our movements in collective action, in the land which feeds us, in a comprehensive estimation of these leaders which acknowledges both their frailty and their holiness?

A Colombian friend once shared with me that as a child, she believed that priests did not urinate — “los padres no mean” (priests do not piss), she remembers thinking in shock when a pastor on a home visit excused himself to the restroom. The popular invocation of King is one that is necessarily uncomfortable with those aspects of his life which violate the stained-glass: his radicalism, his exhaustion with white liberals, his academic plagiarism, and his sexual conduct are notable subjects which quickly hush our cheap praise into silence.

In their song “No Church in the Wild”, Jay-Z and Kanye riff on the spiritual dimensions of political hierarchies: “Human beings in a mob ... what's a mob to a king? what's a king to a god? what's a god to a nonbeliever?” Understandably, in the ongoing atmosphere of vicious slander, mob, and vigilante action against black freedom struggles, the respectable “King to a God” template is a formula many contemporary activists have rejected, opting instead for a more honest look at Martin the man — and for more horizontal organizing models. The Movement for Black Lives, for instance, claims pride in not a “leaderless,” but a “leaderfull” movement, one not explicitly tied to a single savior figure.

How does a despised figure of state surveillance transfigure into an object of adoration and praise, malevolent or facile as some of it may be? In part, perhaps it is because Rev. Martin’s chosen profession as well as his violent end follow a Christlike archetype — a prophet whom, with full knowledge of the lethal consequences of his work, still took up his cross and marched toward Cavalry. This Savior figure is of course prototypically male, able-bodied, and heterosexual. As noted, such ascendancy is often predicated upon a politics of uplift and ascendancy that leaves narrow room for the humanity of the person in question. Such strict templates don’t allow for nuance, for sin, for piss and shit, for non-normative sexualities, for the loud and passionate energy of today’s queer and youth-led uprisings. In King’s own era, civil rights movement architects like Fannie Lou Hamer and Bayard Rustin experienced marginalization for similar reasons.

We are in desperate need for King’s presence among us, and I am saddened when I remind myself that by all accounts he should still be alive today. My grandfather is a healthy 94 — King would be just 90 this year, as would Anne Frank; Emmett Till would be a sprightly 78; all should be reading or gardening or bouncing a grandchild on their lap, telling stories about childhoods spent between struggle and leisure.

Though their spirits remain with us, we have clearly not yet eradicated the demonic forces against which the black freedom movement has waged constant battle. We still live and move and have our being in a world that, in W.E.B. Du Bois’ parlance, celebrates “the all-pervading desire to inculcate disdain for everything black, from Toussaint to the devil”, all while re-deploying radical resistance figures into palatable plastics best suited for fragile palates. Few quotes are taken out of context and used to fuel claims of “reverse-racism” and bash antiracist activists so much as King’s line about aspiring to judgment based on “the content of one’s character”. Yet, nowhere in popular conversation is his critique of whiteness and its impact on vocabulary made known, nor a connection drawn between the ways that whiteness itself deforms, dehumanizes, and diminishes human character and moral witness.

In King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail, he writes to a group of Protestant, Jewish, and Catholic critics that he and his colleagues “would present our very bodies as a means of laying our case ... of purification”. This year, I grieve that certain bodies, still measured against whiteness, are called upon to present themselves as living sacrifices, while others are honored and coddled. I lament that Martin is not with us, and wonder what it would be like if he still was. I am angry that the Spirit which convicted this faithful minister is still smothered as people languish in hellish conditions that Dr. King so powerfully called our attention to. I am saddened that we still uphold the template of maleness, of respectability, as proper indications of leadership.

As a Protestant, King’s view of sainthood would have been rather different than his Catholic peers’. Martin’s 15th century German namesake famously coined the phrase “simul justus et peccator”, or saint and sinner at the same time”, to describe the nature of Christian life in which one strives for the best, yet often fucks up. Luther warned that we have a powerful human tendency to lionize and manipulate the memory of those who have died, and he instructed his flock to “make a distinction between the saints who are dead and those who are yet living”. It is well and proper to remember our heroes and heroines, Luther preached, but “you must turn away from the dead and honor the living saints. The living saints are your neighbors, the naked, the hungry, the thirsty, poor people; those who have wives and children, who suffer shame, who lie in sins. Turn to them and help them.”

It seems clear that our cheap public worship of King has inhibited us from so many things. We have not recognized the soil which nourished this faithful seed; we have ignored the ways King’s legacy is twisted to gloss over ongoing white racism; and we have not actually met the man on that gut, human level — as a person who, like us, embodied radical and centrist tendencies, leaned into both admirable and inadvisable instincts. It is freeing to know that even grand figures such as he can be approached not as stony gods but as treasured friends and courageous colleagues — with burning laughter, questions, and critiques in hand.