I had the story all wrong. I used to say it as a point of pride: "I'm of African American descent from the South." In reality, I am a Filipino American from Seattle. How did I get to this wrong conclusion? Apparently, I did a bit of revisionist history.

From my recollection, my mother told me that there were only two boxes to mark on the marriage license when my parents got married in North Carolina: Black or white. There was no Asian box. The Black box was marked "because we aren't white".

For years I've replayed this conversation over in my mind. I've even used it anecdotally when I wanted to curry favor and maybe a few chuckles at speaking engagements with a large audience of African Americans. It was my way of saying, "We're family."

In over 20 years of youth ministry, I've worked with a wide range of ethnicities and social classes. During those years, I felt God impressing on me the need for justice for African Americans. I believe that what happens with their community does and will affect mine. This call to social justice became stronger when I worked in East Palo Alto, California, with young, single moms, who were mostly Latinas and African Americans. I increasingly identified with Black and Brown issues of race and justice, and later became an ally to the Black Lives Matter movement.

So of course, I was pleased when I thought I had this conversation with my mom. I'm still not sure how I misheard it. But I believed it because it satisfied and affirmed my convictions; if Greensboro, North Carolina considered my parents Black, then I was especially compelled to seek justice for my Black brothers and sisters. We stood on the same margins together.

I found out that I had the story all wrong, when my dad told me, "Nope. White."

"Wait. What? I thought Mom told me you marked Black on your marriage license."

Dad went on to properly recall the story of when they got married in Greensboro in 1970, six years after the Civil Rights Act had passed.

My father was a high school teacher in the Philippines. He worked three jobs, but it wasn't enough. He didn't have any fantasies of the American Dream, but he did know that he could make more money in the U.S. A friend of his retired from teaching after 20 years, and all he could afford was a Jeep so he could pick up scraps of food and sell them to pig farmers. His retirement money could only afford him another job. That wasn't the life my father wanted to live.

Another friend encouraged him to apply for a U.S. visa. At that time, all you needed was a college diploma, a transcript of records, or a residence certificate to show what you did for work. My father had the diploma, so he immigrated to the U.S. with $350 in his pocket. He shared a one-bedroom apartment with six other Filipinos in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco.

Around the same time, my mother was studying at Union Theological Seminary in the Philippines. She had American professors who encouraged her and helped her apply to different Methodist schools in the U.S.; she finally chose Greensboro College. America meant freedom to her. Her plan was to fly to San Francisco with her friend, stay for three days, and then move to North Carolina.

My parents had originally known each other through Methodist youth groups in the Philippines. Through the coordination of mutual friends, my father showed up at the airport with flowers and their courtship began; what was supposed to be a three-day stay became one month. They continued to date when my mom moved to North Carolina, and after a few months, my father moved there too.

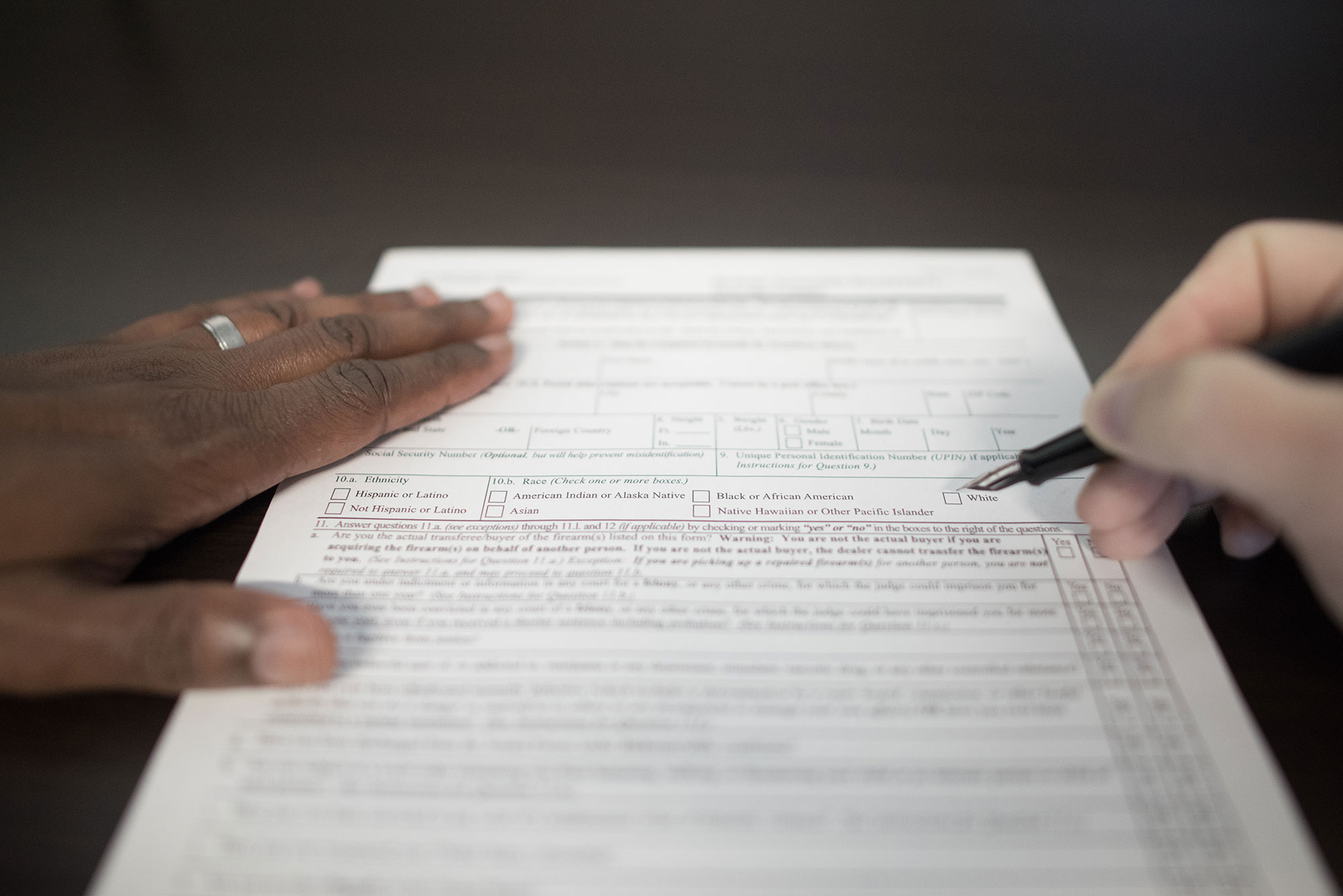

My father closed his eyes as he tried to recall the details. "When I applied for the license to get married, I went to the office that looked like a booth. It had wrought iron on the windows. You speak into the booth to the person filling out the form. When it came to the question of race, it was either Black or white. They fill it out for you. There were only two boxes and you don't get to choose — she looks at you and she determines what you are. I wasn't Black, so she determined I was white!"

When I pressed him for why he thought she chose that box, his answer was, "I'm white enough to be not Black. Besides, I had no choice. It didn't make a difference as far as the license. It was kind of funny because I've never been in that situation before."

I asked my father, "What does it mean to be marked as white in North Carolina?"

He answered, "Probably that means I'm a part of the 'regular' residents. But no one else knows that. You're the only one. It's not something posted on the wall. The application stays in city hall; there's nothing that they issued to show that."

The statement the clerk made that day was much more than a formality. My parents were considered "not Black" — meaning they were not subject to the same kinds of prejudice that African Americans endured. They had what I call "gray privilege": more privilege than Blacks, but at the same time, not having the supremacy of whites. Gray privilege allows people like my parents to pursue their American Dreams while still subjugating them to prejudice and struggles in the pursuit.

My dad could only find what he called menial jobs. He was a janitor, car wash attendant, and movie ticket taker. While he was thankful for any job he could get, these were not careers, and these were jobs that did not pay well. When he applied for a job at the phone company, he asked the hiring manager if he could apply for management since he had experience and a degree. She said no. So he asked for any other job in the company. She said he was overqualified. It was clear that she did not want him there.

But as I pressed my parents for more incidents of racism, they had a hard time identifying with anything the Black community had been experiencing at that time. Instead of being treated maliciously, they were often disregarded rather than outrightly oppressed.

My parents are both devout United Methodists and had attended two different Methodist churches where they were completely ignored by the rest of the church and the pastor.

"They didn't look past us, they looked right through us, like we were not there," my mom recalled. She experienced something similar in the dorms at Greensboro College. She was homesick for any other Asian in a school full of white students. My mother was gracious to give them the benefit of the doubt, "It was my senior year. Maybe they already made their friends and I came too late."

When my mother graduated, they moved to Los Angeles. Five years after arriving in the U.S., they had saved up enough money from working day and night shifts to purchase their first home. My mom experienced her freedom and my dad was able to buy a house and cars for his family — a living testament to the adage of what hard work and an education can do. They are what most would consider the fulfillment of the American Dream.

The tension for me in their story is the idea of gray privilege. When we only consider the Black and white binary, it leaves gray privilege unclear. I have lived with many of the privileges of a white person, but I have also felt the brunt of being ignored, dismissed, and targeted. I have had the opportunity for education and the luxury to pursue dreams and goals without worrying about my safety, but I have also been excluded from leadership positions and other higher profiled opportunities.

I must have heard the story wrong from my mother because I wanted my parents to identify more as Black, because yes, Asian Americans have had our share of being looked through, ignored, or turned down. If we stood on the same margins as Blacks, then we could fight for the same equality.

But the truth of the matter is that they, like many Asian Americans, identify with privilege closer to white people, and I am left more confused on how to make the most of my position as an Asian American. When privilege already lies more in our favor, what would motivate Asian Americans to work toward justice for others as well? What would it look like to fight for the same equality when we are starting at different points of the privilege spectrum?

Joyce Del Rosario is currently a PhD student at Fuller Seminary’s School of Intercultural Studies. She was the executive director of New Creation Home Ministries and an area director for Young Life. Joyce is an active leader with the Christian Community Development Association and on faculty with the Sonoran Theological Group. She enjoys volunteering with Youth First in South Central LA.