Writer Parker Palmer traces his first experience of inner division back to the fifth grade. He describes how his life at home reading stories, building model airplanes, and immersing in fantasies told through the radio were his secret life veiled by a “performed” public life.

In his book, "A Hidden Wholeness", Palmer writes, “My room was a monastic cell where I could be the self with whom I felt most at home — the introspective and imaginative self so unlike the extrovert I played with such anxiety at school.” The pressure to fit in or be liked compelled him to perform a public role that betrayed the rhythms of his private life. Palmer argues that this very personal experience of incongruence eventually becomes the source of both personal and social problems.

As someone who grew up unable to fit in no matter how hard I tried, I had a similar and differing experience from Palmer, as I despised the “secret” life I had at home. I developed disdain for all that was not “white” in my house, in my family, and in me. Of course, this aspirational picture of “white” was highly subjective and romantically colored by television shows such as "Leave it to Beaver", "The Brady Bunch", and later, "Family Ties".

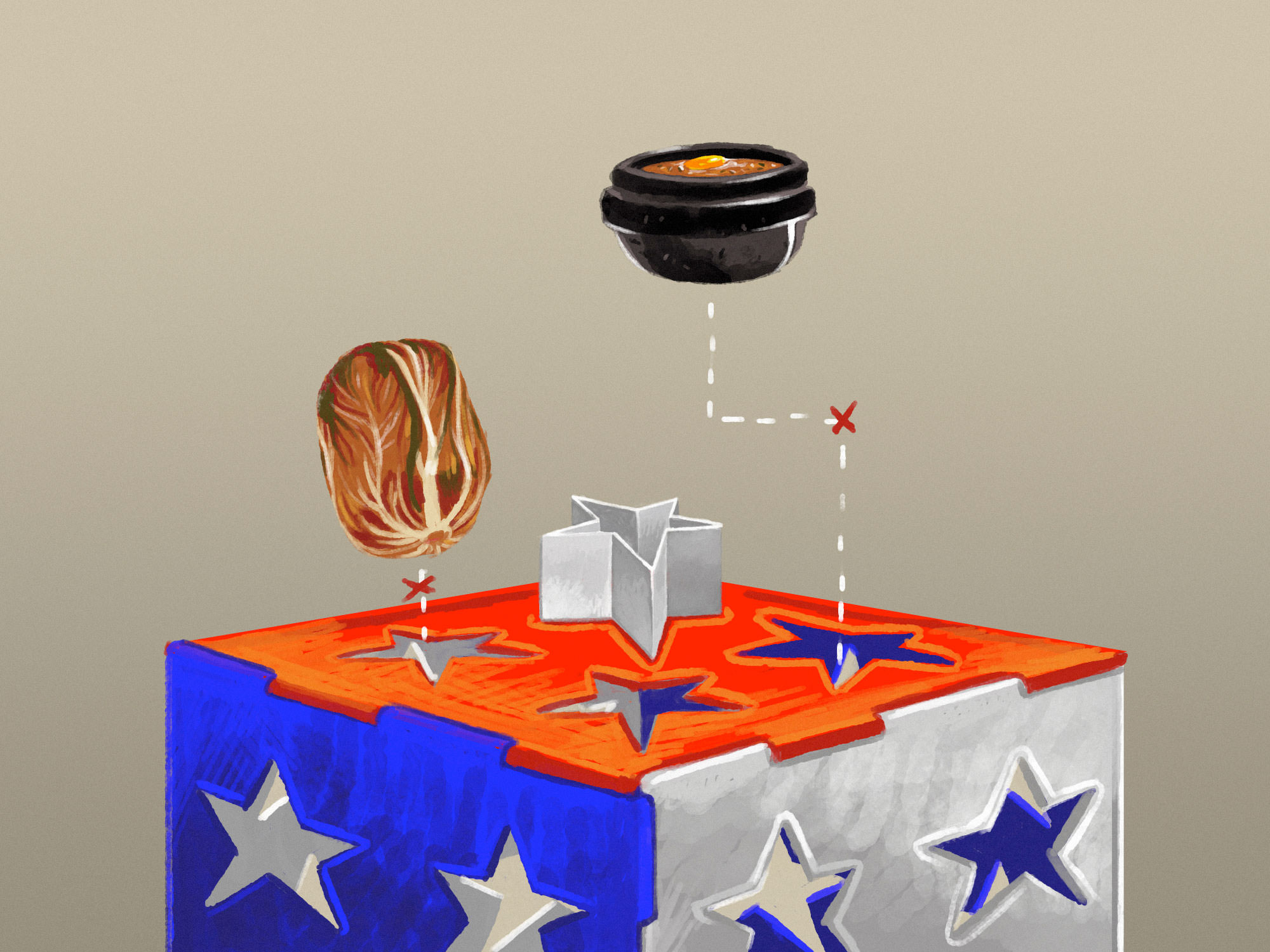

Anything that made me feel less American was a threat to my sense of self-worth — including the Korean food my mother made, our lack of holiday traditions, and a family that did not speak any English in public. I had been indoctrinated by the public master narrative of what “American” looked, smelled, and sounded like, and that narrative implicitly condemned my family of origin to be strange and alien.

Whereas Palmer’s divided secret and public life stayed on parallel lanes, my public life warred with my private one in ruthless rage. I still remember times when I would ignore my mother saying something to me in Korean at the local A & P grocery, if there was a “real American” passing us in the aisle. It was enough to feel different and be treated that way at school every day, I didn’t want the same experience at the supermarket, the laundromat, or at Baskin Robbins.

I cringe as I reflect on these moments of self-loathing. Not only was my family the wrong ethnicity, we were poor and very dysfunctional. It was the perfect storm. My father had another family he would moonlight with while my mom worked tireless hours at a Manhattan sweatshop to pay the bills. My brother and sister chose to be “pro-Korea” as a defense against the ethnic dehumanization that surrounded us like humidity. Their cultural patriotism to all things Korean gave them a sense of rootedness that I did not have. In my case, I was neither Korean nor American, but always trying to become the latter.

A lot of has changed since my childhood, both in my personal life and how society perceives race relations. While I’m sure that incongruence or the divided life is still a social problem, it seems that more people today are at least willing to discuss and work through some of the pressing issues and no longer pretend they don’t exist. While fatherhood (I have four children) and ministry in the local church and in the military have helped me to grow towards wholeness, it was at my local church, Ethnos Community Church in La Jolla, CA, that I learned how hospitality could help shape wholeness.

On Sundays, my family drives 30 miles one way from Camp Pendleton to experience a truly multi-cultural experience in worship. Our songs are routinely sung in Japanese, Chinese, African dialects, Spanish, and other languages. Far beyond tokenism, our intentionally diverse worship is an effort to help people feel at home in their own culture or language while expanding the cultural palette of those from different backgrounds.

After several months of attending worship, it finally clicked for me. The “home” language could be an act of cultural hospitality. It aided people in feeling welcomed, or at least acknowledged for who they are and not who they should aspire to be in white society.

An act of hospitality however, seems to require the host to potentially inconvenience themselves for the sake of their guests. For example, someone who grew up singing only songs by Hillsong in English may initially feel uncomfortable singing an African worship song with a completely different sound, and vice versa. In this vein, the Israelites were commanded to inconvenience themselves and provide many forms of neighborly love to the sojourner, who was basically a type of immigrant or foreign resident (for a few examples, see Ex. 22:21; 23:9; Lv. 19:10; 33–34, Dt. 10:19, Pss. 94:6; 146:9; Je. 7:6; 22:3; Ezk. 22:7, 29; Zc. 7:10; Mal. 3:5).

I sometimes wonder what would be different today if I had grown up in Korea or even Hawaii, where I lived for about one year during high school. I still vividly remember how strange it was to not feel like a minority. To look around and feel at “home”. Like Palmer, I am learning wholeness despite the lack of safe places and social narratives telling me that it’s okay to be "different". The culture at our church has become a tangible expression of going beyond accepting differences to celebrating them. My church is a place where I am learning about cultural hospitality. It is a community that I wish everyone could have, especially the culturally in-between-ers like myself.

The temptation to blend in and be accepted never seems to go away. It just comes in different forms. This journey toward congruence has taught me that accepting myself is not something I can do alone nor simply by reading a good self-help book. It requires others, in the form of hospitable individuals and communities who celebrate my individuality and create space for me to practice self-acceptance. In telling this story, I feel I have bridged some of the divide between who I thought I should be and who I really am. I pray and hope that more of these types of cathartic experiences are experienced and shared in our churches and for our future generations, like my children.

Mark Won is a Navy Chaplain currently stationed in Camp Pendleton, CA where he serves with a Marine unit. Before joining the Navy in 2011, he spent about seven years pastoring in churches in the North East. When he is not spending time with his wife and four children, or writing papers for his D.Min, he enjoys cycling and photography.

John Enger Cheng serves as creative director of Inheritance. He is a Los Angeles-based artist, designer and illustrator. He graduated from the University of Southern California Roski School of Fine Arts and is co-founder of Winnow+Glean. You can see his illustrative work and store at madebyenger.com.