This article is co-written, told from the perspective of Rev. Joseph Yoo.

I had no other choice but to grow up in a Korean immigrant church — my dad was the pastor. Wednesdays, Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays were church days. Wednesday for the midweek service; Friday for youth group when I was old enough; Saturday for Rainbow School (c’mon Korean church folks, you know what I’m talking about); and Sunday for, you know, church.

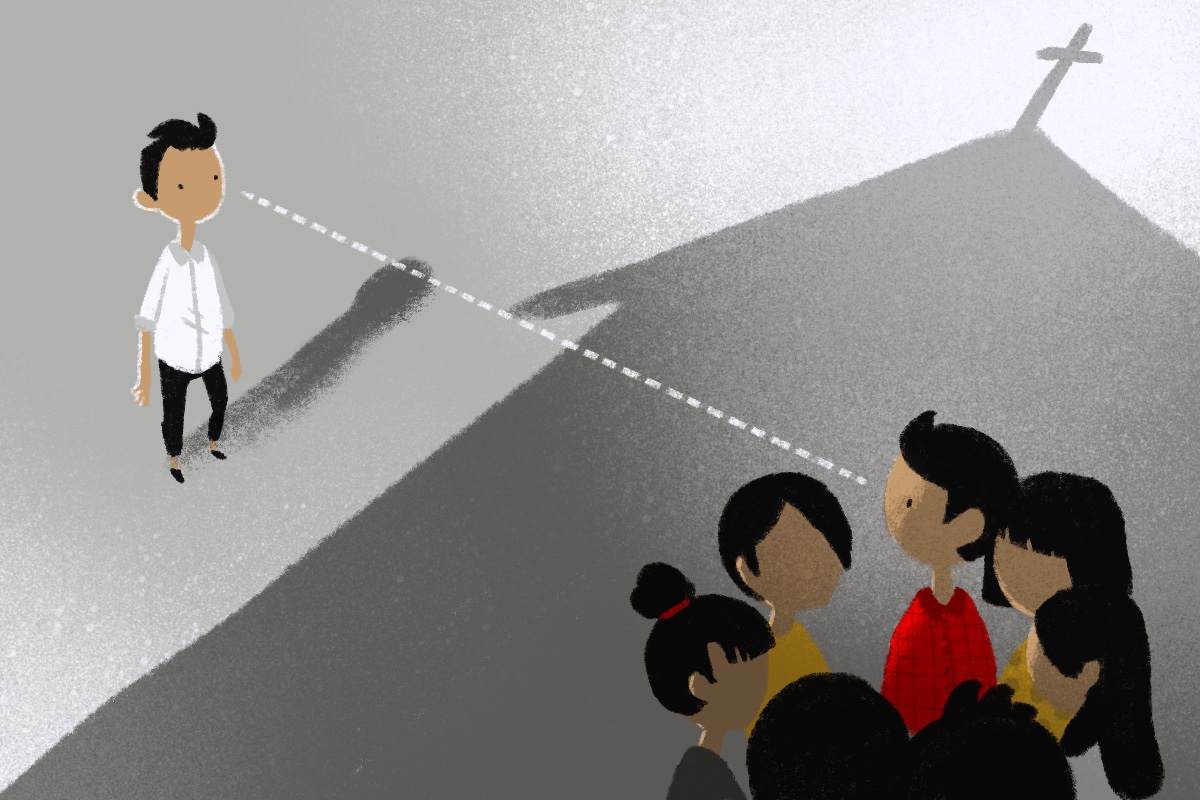

Church was my home away from home. When we lived in South Carolina, church was where I saw people who looked like me. At school, I was always the only Asian in my class, but at church, I was part of the majority. Church was an integral part of my development growing up. I learned about God; I learned about faith; I learned about life; I made lifelong friendships.

As I grew older, I understood the importance of the immigrant church.

The immigrant church is a way to belong without assimilating. You can worship God in your mother language. Just as important (and for some, more importantly), one can be connected with other people who look like them, who share the common bond of language and culture, and thus, still feel connected to the motherland while being so far away from it. One can build relationships for personal or professional reasons.

For many of us, the Korean Immigrant Church became a home away from home.

I predominantly served in the English Ministry (EM) when I served in Korean immigrant churches. EMs served (almost exclusively) Koreans who spoke or were more comfortable with English. At some point, the idea of EM’s begin to grate at me. EMs — whether we were aware of it or not — were always fighting ... something.

We constantly butted heads with the first generation over everything and anything. There were minor things like space issues. The first generation events and ministries always took precedence over the EMs. We fought over budgeting, constantly feeling the need to validate our existence.

But mostly, we fought because of generational differences. We often operated within the immigrant parent-child dynamic: the parent trying to keep the culture of the motherland alive and in the forefront of the child; the child trying to find a new way of living, a new way of doing things. The first generation couldn’t understand why the EM would do something in a certain way and the EM would be frustrated that the first generation seemed to be stuck in the “olden” days and ways.

Yet, the EMs would always be tied to the immigrant church. Most EMs, when I served, were too fragile to be self-sufficient. We were dependent on the mother church to provide space and resources for us. The immigrant church needed us to keep the legacy alive. They wanted their kids to be connected to the church, to God, and to their Korean culture.

A friend of mine often compared the EM and immigrant church dynamic as a 35-year-old who still lives in the basement of the parents home. Both want freedom — the child wants to move out; the parents want the child to move out — but both are afraid of what life would look like without the other.

For me, when we were not fighting with the first generation, we were fighting with one another. I’ve always felt that both the mother church and the EM were resistant to the idea of diversity. We treated church like the clothing brand FUBU: For Us By Us (90’s kids anyone?). The immigrant church was homogeneous out of the necessity of shared language. The Korean immigrant church was exclusively Korean because everything was said and done in Korean. But with the EM, because language was no longer a barrier, there was no pressing need for it to be homogeneous. While the immigrant church was homogeneous out of necessity, the EM was homogeneous out of preference.

While we lived in a diverse neighborhood, EM members never wanted to reach out to our neighbors. They’d rather drive 30 minutes to the local H-Mart to connect with other English-speaking Koreans. That never made sense to me. When there were non-Koreans in our midst, it was quite evident that they did not completely belong. We couldn’t refrain from inside jokes or from using Konglish (combination of Korean and English). Maybe we were so tired of assimilating, we (subconsciously) wanted non-Koreans to find a way to fit in like so many of us had (have) to do. Most EMs were too small in size (and not white enough) to be considered a social country club (like many of our mainline Anglo churches are). We were more like a clique where it became real difficult for others to break through.

But I couldn’t shake off the notion that we were meant for more, to be more. We spoke the language of the majority and we had something to offer: our passion and fire for the love and pursuit of God. We could make such a big impact for the entire city, not just a fraction of it. Why were we limiting ourselves from the work God can do through us? Why were we working so hard to keep the Gospel contained within our homogeneous group? It seemed to go against the Great Commission to go and make disciples of all nations.

During the last three to four years of my service at a Korean immigrant church, a certain theme would rise to permanence in my heart: it doesn’t have to be like this.

I began to grow tired of our preference for homogeneity. I began to grow frustrated with the conflict that would always arise between the immigrant church and the EMs. It was inevitable: we perceived and processed the world differently.

I also began to grow weary of how the Korean immigrant church and its leaders always made themselves susceptible to scandals, corruptions, and behaviors that seemed unbiblical.

I kept reminding myself, it doesn’t have to be like this.

Dae Shik Kim Hawkins Jr. currently lives in Seattle, WA. There he is involved with many advocacy coalitions and community organizing groups. Dae Shik is a freelance writer that covers topics around religion, race, and justice. Some publications that have published his work include Sojourners, Inheritance Magazine, The Establishment, and The Nation.

John Enger Cheng serves as creative director of Inheritance. He is a Los Angeles-based artist, designer and illustrator. He graduated from the University of Southern California Roski School of Fine Arts and is co-founder of Winnow+Glean. You can see his illustrative work and store at madebyenger.com.